There are questions about Ken-Betwa project — some raised by SC committee. MP and UP governments must revisit report.

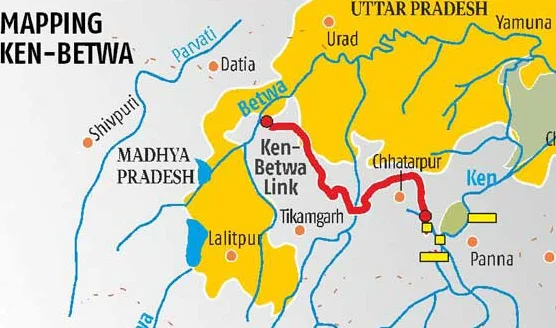

On Monday, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh buried a nearly 40-year-old hatchet to ink an agreement that paves the way for the implementation of independent India’s first major river-linking project. The PRs 37,600 crore scheme, that will transfer water from the Ken river to its fellow tributary of the Yamuna, the Betwa, is seen as a panacea to the water crisis in the Bundelkhand region.

To buy our online courses: Click Here

The Union Jal Shakti ministry claims that the initiative will provide irrigation to 10.6 lakh hectares, supply drinking water to more than 60 lakh people in the two states and generate 103 MW of hydropower. The river linking initiative’s EIA report predicts job opportunities in “construction, fishing and tourism”. On paper, these are good reasons to embark on the project. Two related questions, however, demand urgent answers: Is the idea of transferring the waters of one river to another backed by science? Can the scheme stand scrutiny of an ecologically sound cost-benefit analysis?

Read More: India’s Sri Lanka dilemma

Linking one river to another is not just a matter of transferring water. It means tampering with the ecological functions a river performs when in flow — carrying minerals, nourishing the ecosystems en route, charging groundwater, promoting biodiversity and catering to the needs of people downstream. The Ken performs these functions the best when it’s flooded during the monsoons. But as hydrologists correctly point out, this does not mean that the river has water to spare. Moreover, during most parts of the dry season, the Ken is barely a rivulet. As late as 2016, the river had run dry even during the monsoon season. The annual average-based estimates of the Ken’s water behind the “surplus water” reasoning fail to reckon with such seasonal vagaries in the river’s flow that could aggravate because of climate change.