Drugs & Pharmaceuticals

Introduction

The pharmaceutical industry in India is among the most highly organized sectors. This industry plays an important role in promoting and sustaining development in the field of global medicine. Due to the presence of low cost manufacturing facilities, educated and skilled manpower and cheap labour force among others, the industry is set to scale new heights in the fields of production, development, manufacturing and research. In 2008, the domestic pharma market in India was expected to be US$

10.76 billion and this was likely to increase at a compound annual growth rate of 9.9 per cent until 2010 and subsequently at 9.5 per cent till the year 2015.

The Annual turnover of the Indian Pharma Industry during 2015-16 was 1,85,388 crores during 2015-16. It represented a decline of 7.4% over the correspondence figure for 2014-15 i.e. 2,00,151 crores. The CAGR for last 5 financial years was 8.88%.

The pharmaceutical industry in India is one of the success stories of independent India. It has developed at a phenomenal rate since the 1970s. India has become self-reliant in drugs and has emerged as a major player in the global pharmaceutical industry. It is a source of low-cost quality drugs to the entire world including developed countries such as the USA and Europe.

The lessons that can be drawn from the Indian experience are relevant for the development of the pharmaceutical industry in other developing countries. They also have implications for the industrial policy debate about the role of the government vis-à-vis market.

The patent system has played important role in the pharmaceutical industry. Globally the pharmaceutical industry is dominated by a small number of pharmaceutical companies (MNCs) – Pfizer, Glaxo Smith Kline, Merck, Johnson &Johnson, for example. These MNCs develop new drugs or in-license those developed by others and use the patent system to prevent others from manufacturing and selling them. They also use an elaborate marketing infrastructure to promote the new drugs and to maintain dominant market shares even after the expiry of patents. The large number of remaining pharmaceutical companies is not only much smaller in size compared to the MNCs, they primarily manufacture products for which patents have expired, and are known as generic companies.

But currently, the MNCs do not dominate the pharmaceutical industry in India. In fact India and Japan are the only two countries in the world where Western MNCs do not dominate the pharma industry. Under the Patents and Designs Act 1911, which was in force till 1972, India effectively had a product patent regime in pharmaceuticals. Under this regime, while the MNCs prevented the indigenous companies from producing the new drugs, using the then existing patent law, they themselves were more keen on processing imported drugs rather than developing the industry from the basics. As a result, on the one hand, because of lack of competition, drug prices in India were very high. On the other hand, in the 1970s, India was dependent on imports for many of essential drugs. The import dependence constricted consumption in a country deficient in foreign exchange and inhibited the growth of the industry.

The 1911 Act was replaced by the Patents Act 1970. This eliminated the monopoly power of the MNCs by abolishing product patent protection and providing only process patent protection in pharmaceuticals. The cost-efficient process developed by the Indian generic companies – Cipla, Ranbaxy, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, and others – could be used for manufacturing the latest drugs, introducing them at a fraction of international prices, and dislodging the MNCs from their position of dominance in the domestic market.

The Indian pharmaceutical industry shot to international prominence when it started supplying drugs at low prices for HIV/AIDS. The price charged by the originator company for a three-drug combination (stavidine + lamivudine + nevirapine), which dramatically reduced AIDS deaths in developed countries, exceeded US$10,000 per patient per year till recently. Such pricing made it almost impossible to treat all the patients in developing countries. After Cipla offered to the triple therapy at US$350 (per year), the international prices have crashed making the drugs more affordable and accessible.

It was not only the revision of the patents act, however, that contributed the success of the indigenous pharmaceutical sector. It is important to note that many other countries, for example Ghana, Malawi, Pakistan, Uruguay, and Vietnam, did not provide product patent protection in pharmaceuticals. Despite that, the pharmaceutical industry remained underdeveloped in these countries because they basically lacked the entrepreneurial and technological skills to take advantage of the absence of product patent protection. India is different not only because of its long tradition of drug manufacturing. The entrepreneurial spirit of the indigenous private sector was actively supported through public investment in R&D and manufacturing.

The number of laboratories set up by the Government of India under the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) helped the development of the technological skills necessary for the pharmaceutical industry. In fact, distinctive feature of the pharmaceutical industry in India has been the close collaboration between government laboratories and the private sector.

The setting up of the two public-sector companies – Hindustan Antibiotic Ltd. and Indian Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Ltd (IDPL) – was another important factor in the development of the industry. Though both the companies are now sick, they gave a tremendous boost to indigenous efforts in the private sector and contributed to its success. The city of Hyderabad, where the synthetic drug plant of IDPL was located, has actually developed into the main bulk-drug-manufacturing centre in the country and founders of many bulk-drugs units originally worked for IDPL.

Basic manufacturing by the MNCs too accelerated after the industrial policy restrictions imposed by the government in the 1970s that stipulated that unless they produced bulk drugs in specified ration they would not be permitted to expand in formulations. But in the 1990s as these restrictions were withdrawn, the MNCs started closing down or selling off the plants that they had set up.

Contrary to the common view, India’s experience shows that the state can play a very positive role in the development of indigenous industry. It shows how a country can benefit by regulating the MNCs and supporting the indigenous sector. It exhibits how favourable state policy can help the indigenous sector realize its potential and be competitive vis-à-vis the MNCs.

While the state in India has been successful in realizing the industrial policy objective of developing a strong indigenous sector, it has basically failed in pursuing the health policy objective of ensuring accessibility of drugs to those who need but cannot afford them. For drugs to be accessible it is not enough that prices are lower than the patent-protected monopoly prices. If those who need them cannot afford even lower prices, proper finances should be available to pay for the cost of the drugs. The consumers themselves finance purchase of drugs, by the government, or through private or national insurance agencies. Public-funded health care and/or subsidized insurance not only can counter the market power of the large firms and influence prices; it can also shift the financial burden from the poor who are unable to afford the cost themselves and hence can improve accessibility.

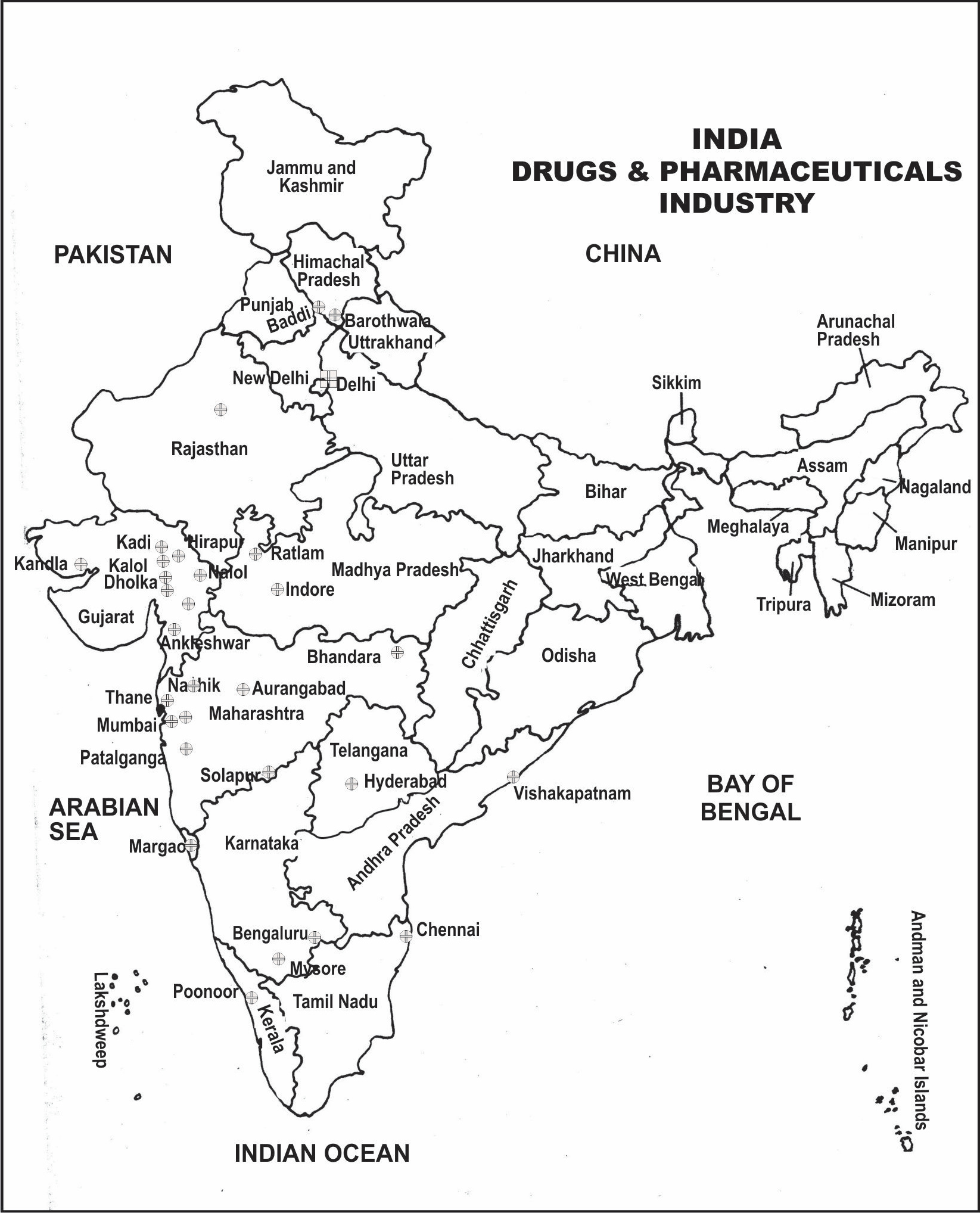

Figure 17.1: Distribution of Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Industry in India

But in India, the involvement of the government of health care is low and health insurance is underdeveloped.

It is true that the absence of product patent protection in India has not been associated with high accessibility of drugs. This does not mean that the presence or the absence of such protection makes no difference. The absence of product patent protection and the presence of multiple producers and sellers provide opportunities that are not possible in a product patent regime. Even if public health and insurance facilities improve, it will be extremely difficult to ensure accessibility of drugs if the patent protected prices are high.

Patent are mandatory in all fields including pharmaceutical products for a minimum period of twenty years under the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) of the World Trade Organization (WTO). In line with TRIPS, India has amended the Patents Act 1970 and again introduced a product patent regime in pharmaceuticals since 1 January 2005.

The Department of Pharmaceuticals had notified the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Policy-2012(NPPP-2012) on 07.12.2012 with the objective to put in place a regulatory framework for pricing of drugs to ensure availability of required medicines – “essential medicines” – at reasonable prices, even while providing sufficient opportunity for innovation and competition to support the growth of industry, thereby meeting the

goals of employment and shared economic well being for all.

Subsequently, to implement the NPPP-2012, the new Drugs (Prices Control) Order, 2013 was notified on 15.05.2013 to control the prices of specified dosages and strengths as under National List of Essential Medicines-2011(NLEM-2011). This was modified to include medicines included in NLEM-2015 vide notification dated 10.03.2016 after the same was received from Ministry of Health & Family Welfare who had constituted an Expert Core Committee to review and recommend the revision of National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM-2011) in the context of contemporary knowledge of use of therapeutic products.

But the protection of the private rights of the patentees is not the sole concern of TRIPS. It also recognizes the underlying public policy objectives and the special needs of the developing countries to permit flexibilities in implementing its provisions. Compulsory licensing is the most important flexibility permitted under TRIPS. A compulsory license (CL) is an authorization by a government to non-patentees but on payment of royalties to the latter. A properly administered CL system is of vital importance in promoting competition and hence lowering prices while ensuring that patentees get compensation through royalties. In fact, CL is one of the ways in which TRIPS attempts to strike a balance between promoting access to existing drugs and promoting R&D in new drugs.

The remarkable success of the Indian pharmaceutical industry has evoked the optimism that the growth in exports of patents-expired drugs will more than compensate for the decline in domestic opportunities as Indian companies are prevented from producing the new drugs developed abroad. But a steady and stable home market is of fundamental importance for success abroad. What is often not appreciated is that the remarkable export growth of the larger Indian companies in recent years has been accompanied by an equally remarkable domestic growth. It will be very difficult for Indian companies to sustain the export dynamism in the absence of a growing domestic market.

For the steady growth of the Indian generic companies, it is important to devise measures so that they can continue to manufacture and sell the new-patented products in the domestic market. As mentioned earlier, this is possible within TRIPS by having a simple and easy-to-use CL procedure. So far as new drugs are concerned, apart from CL, the option is for Indian companies to develop new drugs themselves or collaborate with MNCs. Some Indian companies have stared R&D for new drugs. But because they do not have all the skills and the funds, the model they have adopted is to develop new molecules and licence these out to MNCs at early stages of clinical development. A number of Indian companies are very optimistic about the prospects of increasing marketing and manufacturing alliances with MNCs in the new product patent regime. Outsourcing by MNCs to Indian companies has started but the present size is still modest.

Industry Trends

The pharma industry generally grows at about 1.5-

1.6 times the Gross Domestic Product growth.

- Globally, India ranks third in terms of manufacturing pharma products by volume.

- The Indian pharmaceutical industry has grown at a rate of 9.9 % till 2010 and after that 9.5 % till 2015.

- Indian export of drugs is generally worth over US$8 billion in to the US and Europe followed by Central and Eastern Europe, Africa and Latin America.

- The Indian vaccine market which was worth US$665 million in 2007-08 is growing at a rate of more than 20%.

- The retail pharmaceutical market in India is expected to cross US$ 15 billion by 2018.

Problems and Challenges

Every industry has its own sets of advantages and disadvantages under which they have to work; the pharmaceutical industry is no exception to this. The pharmaceutical industry remains beset with problems, for most of which there do not appear to be obvious solutions.

Although it has exclusive rights to the sale of a new drug during its patent life, some of the challenges the industry faces are:

Regulatory obstacles

Increasing regulation is leading to additional costs and longer development times with consequently reduced times to patent expiry.

Lack of proper infrastructure

Increasing Infrastructure cost pressures within national health services are leading to progressive downward pressure on prices.

Lack of qualified professionals

Increasing non-competence of the executive management teams is contributing to a slowdown in the appearance of novel pharmaceuticals.

Expensive research and development

Many people consider that the current research pharmaceutical business model is no longer sustainable, but no-one has yet come up with a better one.

Lack of academic collaboration

Market related problems

Market penetration by generics is increasing rapidly. Reducing risk tolerance in patient populations and regulatory bodies is leading to a lower success rate for marketing authorisation approvals.

Government Initiatives

The government of India has undertaken several including policy initiatives and tax breaks for the growth of the pharmaceutical business in India. Some of the measures adopted are:

- Pharmaceutical units are eligible for weighted tax reduction at 150% for the research and development expenditure obtained.

- Two new schemes namely,

- New Millennium Indian Technology Leadership Initiative, and

- The Drugs and Pharmaceuticals Research Program have been launched by the Government.

- The Government is contemplating the creation of SRV or special purpose vehicles with an insurance cover to be used for funding new drug research.

- The Department of Pharmaceuticals is mulling the creation of drug research facilities, which can be used by private companies for research work on rent.

Foreign Direct Investment in Pharmaceuticals Sector

Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion has reviewed the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) Policy and vide their Press Note No. 5 (2016 Series) dated 24/06/2016 has amended the FDI Policy whereby Pharmaceutical Companies for Greenfield Pharma Projects can invest 100% FDI through automatic route and for Brownfield Pharma Projects foreign investment upto 74% is allowed under automatic route and beyond that the companies have to come through government route.

Cluster Development Programme for Pharma Sector (CDP-PS)

With a vision to catalyze and encourage quality, productivity and innovation in pharmaceutical sector and to enable the Indian Pharmaceutical Industry especially SMEs to play a leading role in a competitive global market, Hon’ble Minister of Chemicals and Fertilisers approved the introduction of Cluster Development Programme for Pharma Sector (CDP-PS) on 27.10.2014. The CDP-PS is a

Central Sector Scheme. The total size of the scheme is proposed as Rs.125 Crores for CDP- PS for 12th Five Year Plan. Assistance under the Scheme will be Rs. 20.00 Crore per cluster or 70% of the cost of the project, whichever is less for creation of common facilities. Some of the indicative activities under the Common facilities are:

- Common Testing Facilities

- Training Centre

- Effluent Treatment Plant

- R&D Centres

- Common Logistics Centre

Projects and Development India Limited (PDIL) who was chosen as the Project Management Consulting (PMC) for implementing the scheme had called EOIs and after processing the same, Scheme Selection Committee (SSC) has selected the proposal of M/s Chennai Pharma Industrial Infrastructure Upgradation Company, Alathur, Chennai, and Tamil Nadu. Further, the proposal of M/s Andhra Pradesh Industrial Infrastructure Corporation (APIIC) Limited along with other proposals received is being examined by PDIL.

Scheme for Financing Common Facility Centres (CFCs) at Bulk Drug Park

The vision of the Department of Pharmaceutical (DoP), Ministry of Chemicals & Fertilizers is to catalyze and encourage quality, productivity and innovation in Bulk Drug Sector and to enable the Indian Bulk Drug Industry to reduce the dependency on import of Bulk Drugs. For this, world class quality manufacturing facilities with high level of productivity with innovative capabilities are required. However, these are on one hand very capital intensive and cannot be established and opened by Bulk Drug Manufacturing Units on their own due to financial constraints.

In this direction, the Department proposes in the first instance to start a scheme for Financing Common Facility Centres (CFCs) at 3 Bulk Drug/API Parks in the country at a total cost of Rs. 450 crores.

Indian Medical Device Industry

In September 2014, the Indian Government launched the “Make in India” campaign, with the objective of making India a global manufacturing hub; thus, bringing foreign technology and capital into the country. Accordingly, a Task Force was formed under the Chairmanship of Secretary, Department of Pharmaceuticals (DoP), to address issues relating to the promotion of domestic production of high end medical device in the country. The Task Force in its report released on 8th April 2015 had made a set of recommendations for the promotion of medical device industry in the country. The Indian medical device market has grown from USD 2.02 billion (INR 13,130 crores) in 2009 to USD 3.9 billion (INR 25,259 crores) in 2015 at CAGR of 15.8%. This accounts for approximately 1.7% of the global medical device market in 2015. The Indian Medical Device market contributes to 4% of the Indian healthcare market which is pegged at USD 96.7 billion (INR 6.29 Lakh crores), in 2015. The industry estimate suggests that the Indian medical device market will grow to USD 8.16 billion (INR 53,053 crore) in 2020 at CAGR of 16%.

Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana.

The Jan Aushadhi Scheme was launched in the year 2008 with the aim of selling affordable generic medicines through dedicated sales outlets

i.e. Jan Aushadhi Stores in various districts across the country. Some of the objectives of the scheme are as follows:-

-

- Ensure access to quality medicines.

- Extend coverage of quality generic medicines so as to reduce and there by redefine the unit cost of treatment per person.

- Create awareness about generic medicines through education and publicity so that quality is not synonymous with only high price.

- Be a public programme involving Government, PSUs, Private Sector, NGO, Societies, Co-operative Bodies and other Institutions.

- Create demand for generic medicines by improving access to batter health care through low treatment cost and easy availability wherever needed in all therapeutic categories.

The first Jan Aushadhi Store was opened at Amritsar in Punjab in November 2008. The original target of the campaign was to establish Jan Aushadhi Stores in every district of our country.

Recently, “Pradhan Mantri Jan Aushadhi Yojana” (PMJAY)has been renamed as “Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana” (PMBJP) and “Pradhan Mantri Jan Aushadhi Kendra” (PMJAK) as “Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Kendra” (PMBJK).

Bureau of Pharma PSUs of India (BPPI):

BPPI is an independent society set up by the Department of Pharmaceuticals, Ministry of Chemicals & Fertilizers in December, 2008. BPPI’s mission is to make generic medicines available for all. BPPI is responsible for proper monitoring and functioning of Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Kendras.

Progress during 12th Five-year Plan period:

As on end March 2012, only 112 Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Kendra (PMBJK) could be opened. To have an accelerated growth of the campaign, a New Business Plan was released during August 2013 with an ambitious target of opening 3000 PMBJK by the end of 2016-17. The plan also contained certain changes in the Revamped Jan Aushadhi Scheme 2015:

Effective implementation of Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Pariyojana (PMBJP) has been analyzed through organizing brain storming sessions and discussions with various stake holders and BPPI submitted their Strategic Action Plan (SAP 2015) to achieve the objectives set by the Government. Key areas of significance identified are Availability, Acceptability, Accessibility, Affordability, Awareness and Effective Implementation of the Scheme. Accordingly, a new Strategic Action Plan was prepared and the same was approved during September, 2015.

Financial support to Pradhan Mantri Bhartiya Janaushadhi Kendra (PMBJK):

-

- An amount of Rs. 2.5 lakhs shall be extended to NGOs/agencies/individuals establishing PMBJK in government premises like hospitals/ medical colleges/Railways/Sate Transport/ Co- operation/ Municipalities/ Post offices, etc. where space is provided free of cost by Government to operating agency:

- Rs. 1 lakh reimbursement of furniture and fixtures.

- Rs. 1 lakh by way of free medicines in the beginning Rs. 0.50 lakh as reimbursement for computer, internet, printer, scanner, etc.

- PMBJK run by private entrepreneurs/ pharmacists/ NGOs/ charitable organizations that are linked with BPPI headquarters through internet

- Shall be extended an incentive up to Rs. 2.5 lakhs. This will be given @ 15% of monthly sales subject to a ceiling of Rs.10,000/- per month up to a limit of Rs. 2.5 lakhs.

-

- In North Eastern States, i.e., Naxal affected areas and Tribal areas, the rate of incentive will be 15% and subject to monthly ceiling of Rs. 15,000 and total limit of Rs. 2.5 lakhs.

- The Applicant belonging to weaker section like SC/ST/Differently-abled maybe provided medicines worth Rs. 50,000/- in advance within the incentive of Rs. 2.5 lakhs which will be provided in the form of 15% of monthly sales subject to a ceiling of Rs. 10,000/- per month up to a total limit of Rs.2.5 lakh.

- Trade margin to retailers and distributors: Trade margins have been revised from 16% to 20% for Retailers and from 8% to 10% for Distributors.

Pharma Export

In the recent years, despite the slowdown witnessed in the global economy, exports from the pharmaceutical industry in India have shown good buoyancy in growth. Export has become an important driving force for growth in this industry with more than 50 % revenue coming from the overseas markets.

Exports of pharmaceuticals products from India increased from US$6.23 billion in 2006-07 to US$8.7 billion in 2008-09 a combined annual growth rate of 21.25%. Some of the major pharmaceutical firms include Sun Pharmaceutical, Cadila Healthcare and Piramal Enterprises.

India exported $11.7 billion worth of pharmaceuticals in 2014.

Future of Pharmaceutical Industry

It is estimated that the Indian pharmaceutics market will grow to USD 55 billion by 2020 driven by a steady increase in affordability and a step jump in market access. At the projected scale, this market will be comparable to all developed markets other than the US, Japan and China. Even more impressive will be its level of penetration. In terms of volumes, India will be at the top, a close second only to the US market. This combination of value and volume provides interesting opportunities for upgrading therapy and treatment levels.

However, pricing controls and an economic slowdown can wean away investments and significantly depress the market, allowing it to reach only USD 35 billion by 2020. But the market has the potential to reach USD 70 billion, provided industry puts in super normal efforts behind the five emerging opportunities, and enhances access and acceptability in general.

The mix of therapies will continue to gradually move in favour of specialty and super-specialty therapies. Not with standing this shift, mess therapies will constitute half the market in 2020. Metro and Tier-I markets will make significant contributions to growth, driven by rapid urbanisation and greater economic development. Rural markets will grow the fastest driven by step- up from current poor levels of penetration. On balance, Tar-II markets will get marginally squeezed out. The hospital segment will increase its share and influence, growing to 25 per cent of the market in 2020, from the current 13 per cent. Finally, the five emerging opportunities will grow much faster than the market, and will have the potential to become a USD 25 billion market by 2020.

Over the past 5 years, the distinction between local players and multinational companies has increasingly blurred. It is believed that if market leadership is the aspiration, the implications and imperatives will be common for both groups of players. They will need to strengthen three sets of commercial capabilities: marketing excellence, sales force excellence, and commercial operations. In addition, players will need to put in place two enablers: strengthen the organisation to be able to sustain performance and manage rising complexity; and collaborate with stakeholders within and outside the industry to drive access and shape the market.

The government also will need to make investments to expand access to healthcare, while ensuring that industry remains viable and competitive.