Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev listens during a joint press conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel prior to a meeting on Jan. 21, 2019, in Berlin. Tashkent’s engagement with the world presents both good and bad for Uzbekistan.

· Under President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Uzbekistan is abandoning its traditional isolationism and becoming an increasingly important player in the dynamic relationship among Russia, China and, to a lesser degree, the U.S.

· Uzbekistan will be more open to increasing economic and security ties with Russia, even as it makes parallel overtures to China and Western countries to diversify its foreign policy.

· Tashkent’s transformation will play an important role in fostering greater economic and security cooperation within Central Asia.

For years, isolationism guided Uzbekistan’s interactions with the wider world. Now, however, reforms stemming from a political succession in Central Asia’s most populous country are reverberating far beyond Tashkent. As part of its political evolution, Uzbekistan has strengthened cooperation within Central Asia while also becoming an increasingly attractive partner for Russia, China, and the United States as they engage in a strategic competition for influence and investment in the region. The opening presents significant opportunities for Uzbekistan to expand its economic and security outreach to its neighborhood, yet the changes also pose risks, as the competition among these larger powers could pull the country in directions it doesn’t want to go.

Uzbekistan’s only transfer of power occurred in 2016, when septuagenarian President Islam Karimov, who had maintained an iron grip over the country since the late Soviet era, died. Karimov was succeeded by his longtime prime minister, Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who initially stayed the course in terms of policy, but more than three years after the strongman’s death, the new president is taking Uzbekistan in a new direction.

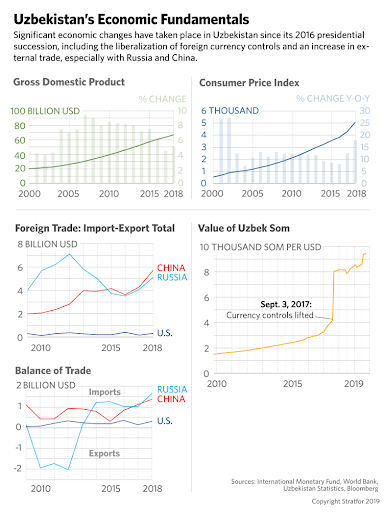

Mirziyoyev’s first major act was to liberalize the country’s foreign currency conversion peg. Under Karimov, the government in Tashkent maintained heavy restrictions on the conversion of Uzbek som into dollars; few people apart from the politically well-connected could convert money, producing a high discrepancy between the official conversion rate (4,000 som to the dollar) and the black market rate (8,000). In September 2017, however, Miziyoyev lifted the fetters, effectively merging the rates. While that increased inflation in the short term, it significantly improved the business environment and extended convertibility to average citizens, leading to substantial economic gains.

View our Blog: https://ensembleias.com/blog/

Next, Mirziyoyev liberalized the country’s visa process in an effort to attract more tourists and foreign investment. Uzbekistan granted the citizens of nearly 100 nations visa-free access and implemented a streamlined an e-visa process that eased arrivals for others, including from the United States. That led to a doubling of tourism revenues (which constitute more than 3.4 percent of gross domestic product) from roughly $500 million in 2016 to over $1.1 billion in 2018 and raised investment as a percentage of GDP to 38 percent, a double-digit increase from previous years.

Next, Mirziyoyev liberalized the country’s visa process in an effort to attract more tourists and foreign investment. Uzbekistan granted the citizens of nearly 100 nations visa-free access and implemented a streamlined an e-visa process that eased arrivals for others, including from the United States. That led to a doubling of tourism revenues (which constitute more than 3.4 percent of gross domestic product) from roughly $500 million in 2016 to over $1.1 billion in 2018 and raised investment as a percentage of GDP to 38 percent, a double-digit increase from previous years.

Ending Isolation

These domestic reforms paralleled Uzbekistan’s efforts to improve its relations with its neighbors. Under Karimov, Uzbekistan navigated an especially fraught relationship with other Central Asian states, particularly Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, with which it shares the strategic yet contested Fergana Valley region. Disputes over border demarcation and water resources produced regular confrontations among the three, contributing to major political instability and periodically leading to violent protests and ethnic clashes. Mirziyoyev has made efforts to better demarcate the countries’ intricate borders, reducing the number of disputes that marked the Karimov era, while also collaborating on water sharing. This, in turn, has led to a significant increase in inter-regional trade turnover, which rose more than 27 percent in the first five months of 2019 compared to 2018.

But perhaps the most substantial shift under Mirziyoyev is the end to Uzbekistan’s isolationism when it comes to the major external powers in the region. Unlike Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan under Karimov chose not to join Russia’s alliance network through blocs like the Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Eurasian Economic Union (Tashkent was, however, briefly a member of the former before pulling out) and chose to keep Moscow and Beijing at an arm’s length, fearing their overbearing political influence. Moreover, in 2005, Uzbekistan kicked the United States out of an air base in Karshi that the U.S. military had been using for logistical operations in Afghanistan after Washington criticized Tashkent over human rights abuses in that year’s Andijan massacre.

All these measures preserved the country’s neutrality, but they also inflicted a substantial cost, as Uzbekistan missed out on foreign investment and economic growth even though it enjoys, by regional standards, a relatively diversified resource base with supplies of oil, natural gas, minerals, and cotton and other agricultural products. Mirziyoyev sought to rectify the issue by pursuing economic reforms and signing a number of trade and investment deals with Russia, China and, to a lesser extent, Western countries benefitting the energy, transport, telecommunications, banking and other sectors. The president also indicated a willingness to pursue greater security cooperation with his larger neighbors, resuming joint military exercises with Russia for the first time in more than a decade and cooperating on counterterrorism operations with Moscow and Beijing.

The Cost of Opening Up

Given Uzbekistan’s size, resources and strategic location, its recent transformation has had an impact not only within the country but across the wider region. Nevertheless, the reform efforts have not come without obstacles or unintended consequences. Initially, the greatest pushback to Mirziyoyev’s reforms came from the country’s pervasive National Security Service (SNB), which wielded significant power under Karimov. The SNB and its leader, Rustam Inoyatov, was far more conservative and resistant to reforms, delaying the economic and visa liberalization efforts. Mirziyoyev, however, persevered, gradually removing obstacles in the SNB before finally dismissing Inoyatov at the beginning of 2018, clearing the way to push his reforms through. Unsurprisingly, however, bureaucratic inertia persists, and elements within the security services continue to oppose Mirziyoyev’s initiatives.

Another challenge that Uzbekistan faces in implementing economic reform and attracting large-scale foreign investment is structural. Given that the country’s centralized economy has proceeded for decades with few changes, the privatization process has been exceedingly slow; in fact, more than 85 percent of companies in the country remain state-owned, as the government retains a controlling stake in all sectors it deems strategic. Considering enduring challenges over the rule of law and mid- and lower-tier civil servants’ lack of familiarity about how to implement reforms, it will likely take years before Uzbekistan can attract significant foreign — especially Western — investment. This will give Russia and China and their large state-owned enterprises an advantage in reaping the benefits of Uzbekistan’s opening and gaining greater access to its resources, although Tashkent does not want to exclude other investment partners, especially from the United States and Europe.

As Uzbekistan opens up, competition between Moscow and Beijing over its alignment is likely to increase, making it a source of friction and potential confrontation between Russia and China down the line.

On the foreign policy side, the same opening that has attracted greater involvement from Russia and China could also foster greater competition between them as they both strive to increase their influence in Uzbekistan. Russia, in particular, has reinvigorated its efforts to pull Uzbekistan into its orbit via the Eurasian Economic Union; Tashkent has said it is studying the prospect, but it is nevertheless likely to resist for fear of losing its maneuverability and undermining cooperation with other powers, such as China — especially given Uzbekistan’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative. Ideally for Uzbekistan, Tashkent could improve economic and security ties with all major external powers while preserving its autonomy and eschewing membership in foreign-led blocs as part of a multivector foreign policy. But as Uzbekistan opens up, competition between Moscow and Beijing over its alignment is likely to increase, making it a source of friction and potential confrontation between Russia and China down the line. That, naturally, could foment political instability, put investments at risk and disrupt — or even reverse — Uzbekistan’s outreach and emergence from isolation.

In the end, the reform process has produced both significant opportunities and looming challenges for Uzbekistan. As Mirziyoyev’s government initiates further changes — from banking and tax reform to further travel and currency liberalization — the proposals will test how much the country is truly willing to come in from the cold, just as the competition over Tashkent’s alignment and orientation will only intensify among the great powers.

Visit our store at http://online.ensemble.net.in