Crop diversification policy must address nutritional challenges, bring agriculture in sync with environmental demands

An optimal agri-food policy should look at issues pertinent to not only the short run but also try to address medium to long-term challenges.

Framing an optimal agri-food policy in India is the need of the hour. The policy should look at issues pertinent to not only the short run but also try to address medium to long-term challenges. UN population projections (2019) indicate that India is likely to be the most populous country by 2027. By 2030, the country is likely to have almost 600 million people living in urban areas, who would need safe food from the hinterlands. Indian agriculture has an average holding size of 1.08 hectare (2015-16 data), while engaging 42 per cent of the country’s workforce. Cultivable land and water for agriculture are limited and already under severe pressure. Given these basic parameters, how does one design an optimal agri-food policy?

Such a policy must have at least four touchstones. One, it should be able to produce enough food, feed and fibre for its large population. Two, it should do so in a manner that not only protects the environment — soil, water, air, and biodiversity — but achieves higher production with global competitiveness. Third, it should enable seamless movement of food from farm to fork, keeping marketing costs low, save on food losses in supply chains and provide safe and fresh food to consumers. And, finally, consumers should get safe and nutritious food at affordable prices. At the centre of all these is the farmer, whose income needs to go up with access to best technologies and best markets in the country, and abroad.

On the production front, the best policy is to invest in R&D for agriculture, and its extension from laboratories to farms and irrigation facilities. It is believed that developing countries should invest at least one per cent of their agri-GDP in agri-R&D and extension. India invests about half. It needs doubling with commensurate accountability of R&D organisations, especially the ICAR and state agriculture universities to deliver. Can it be done over say next three years?

India’s critical failing has been the inability to protect its natural resource endowments, especially water and soil. Free electricity for pumping groundwater and highly subsidised fertilisers, especially urea, are damaging groundwater levels and its quality, especially in the Green Revolution states of Punjab, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh. This region is crying for crop diversification, especially reducing the area under rice by almost half, while augmenting farmers’ incomes.

This can be done by switching from the highly subsidised input price policy (power, water, fertilisers) and MSP/FRP policy for paddy, wheat and sugarcane, to more income support policies linked to saving water, soil and air quality. But policymaking so far on this front has failed, resulting in excessive production of these three crops in the country. Sugar and wheat are being produced at prices higher than global prices, and these crops can’t be exported unless they are heavily subsidised. Excessive stocks of wheat and rice with the Food Corporation of India (FCI) are putting pressure on the agency’s finances. Rice remains globally competitive, but it should be remembered that in exporting rice we are also exporting massive amounts of precious water — almost 25-30 billion cubic meters, annually. This is the water that is pumped for rice cultivation, enabled by subsidised power supply. All these are signs of sub-optimal agri-food policies.

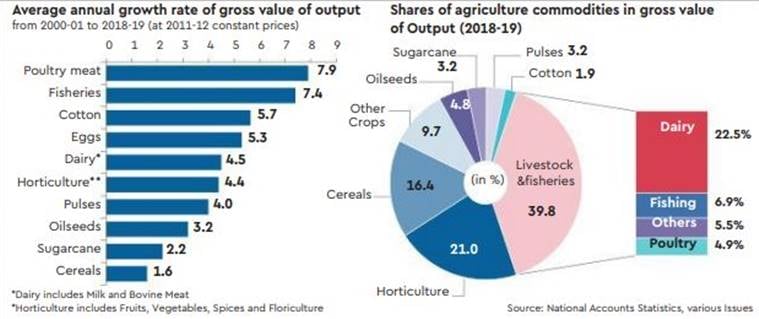

Interestingly, these are the three crops in which MSP/FRP has any significant meaning, but they are growing at the slowest pace (see Figure 1). Poultry, fishery, dairy, and even horticulture, for which there is no MSP, are growing much faster — three to five times — than cereals or sugarcane. It may be noted that in 2018-19, the value of livestock and fishery was almost 40 per cent of the gross value of agricultural output. Horticulture accounted for another 21 per cent (see Figure 2). Overall, the total value of purchases by government agencies at MSP of paddy, wheat, pulses, oilseeds and cotton, was just about 6 per cent of the value of the total agriculture and allied sector.

In the marketing segment also, for most of our agri-commodities, our costs remain high compared to several other developing countries due to poor logistics, low investments in supply lines and high margins of intermediaries. This segment has been crying for reforms for decades, especially with respect to bringing about efficiency in agri-marketing and lowering transaction costs. It is still a tall challenge before us.

Let us now look at matters from the perspective of consumption. Basic hunger has been more or less conquered, but the biggest challenge for next 10 years is that of malnutrition, especially amongst children. It is a multi-dimensional problem. From women’s education, to immunisation and sanitation, to nutritious food, all have to be addressed on a war footing. The public distribution of food, through PDS, that relies on rice and wheat, and that too at more than 90 per cent subsidy over costs of procurement, stocking and distribution, is not helping much. It is already blowing up the finances of FCI, whose borrowings have touched Rs 3 lakh crore. The Finance Minister will do an honest job if she puts the full food subsidy bill in the central budget rather than putting it under the carpet of FCI borrowings. But, more importantly, beneficiaries of subsidised rice and wheat need to be given a choice to opt for cash equivalent to MSP plus 25 per cent. The FCI adds about 40 per cent cost over the MSP while procuring, storing and distributing food. This cash option will save some money to the FM and also lead to supplies of more diversified and nutritious food to the beneficiaries.

All this would mean setting agri-food policies on a demand-driven approach, protecting sustainability and efficiency in production and marketing, and giving consumers more choice for nutritious food at affordable prices.

This article first appeared in the print edition on January 18, 2021, under the title “A balanced diet”. Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture at ICRIER