This photo from Feb. 25, 2017, shows the construction site of the second mooring facility of the Yamal LNG plant in the village of Sabetta. Russia’s future prosperity depends in part of the Arctic’s resources, but getting them to market will be easier said than done.

· Despite the Kremlin’s encouragement, state-owned oil and gas enterprises are likely to remain hesitant to commit resources to the

costly development of Arctic assets.

· Moscow will try to reduce the financial burden of building Arctic infrastructure, but its proclivity to offer incentives on a case-by-case basis will hamper rapid development.

· In the end, the output from the Arctic could fall short of government targets to ensure sustained oil production levels and overall economic growth.

The Russian Arctic is warming, but the Kremlin’s dreams for the region remain in the deep freeze. Since planting its flag on the seafloor at the North Pole in 2007, Moscow has reinforced its territorial claims in the Arctic by increasing its military presence and bolstering its icebreaker fleet. But Russia’s progress in making use of the Arctic’s mineral and hydrocarbon resources and unlocking the rest of the region’s economic potential is stalling.

Apart from some large initial gains through the Yamal liquified natural gas project, the tremendous investments required to bring infrastructure to the Arctic have begun to lag projections as the government struggles to motivate state-owned and private corporations to go north. The lack of sufficient ports, railroads, electricity grids, airports and more in the Arctic has significantly increased the cost of individual projects at a time when the government is facing budgetary constraints and popular opposition to rising taxes. Moscow, accordingly, is putting the onus for developing Arctic infrastructure almost entirely on private and state-owned entities. Unsurprisingly, corporations have been reluctant to foot the bill for such large, upfront investments, meaning progress has become bogged down as the sides haggle over tax breaks or financial support. Ultimately, cost, feasibility and the like could well put paid to Russia’s hopes of scoring an Arctic windfall.

View our Blog: https://ensembleias.com/blog/

Tapping the North’s Energy Riches

According to the Kremlin, Moscow’s Arctic infrastructure plans will require investments of over $200 billion between now and 2050; more crucially, around $87 billion of that would have to occur by 2024. Moscow, however, has earmarked only $14 billion for the plans over the entire period — a figure that by far trails spen

ding ($400 billion) for projects like military modernization. (Officials in the Economy and Energy ministries have criticized the emphasis on the military, warning that the incentives for Arctic development were insufficient.)

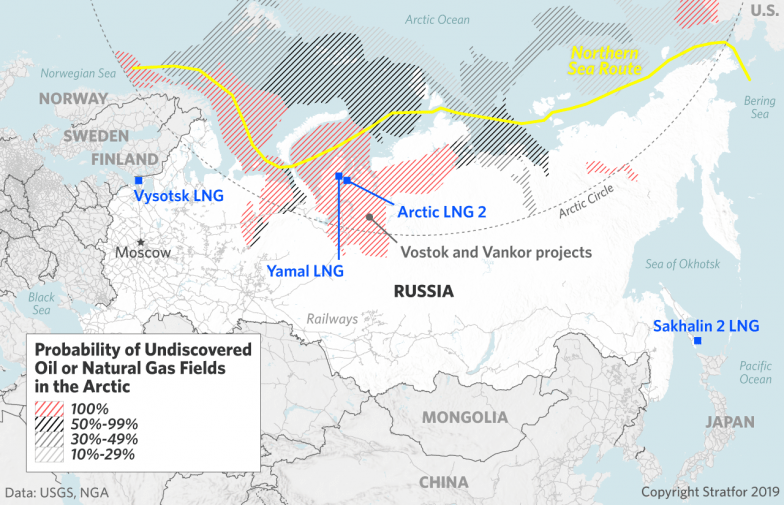

One of Russia’s main pursuits in the Arctic has been the development of oil and natural gas. Areas north of the Arctic Circle are believed to hold over 90 billion barrels of oil and more than 42 billion cubic meters of natural gas, about 80 percent of which lies in Russian-claimed territories. For Russia, the development of the

se resources is crucial. Many Russian oil and gas fields currently under production will head into decline starting next year, according to official predictions, driving urgency for greater development in the Arctic. Given that the oil and gas sector provides about 40 percent of government revenue, the Kremlin will be severely strapped for cash if Arctic development fails to get off the ground.

Moscow has earmarked only $14 billion for its Arctic development plans — a figure dwarfed by spending for projects like military modernization.

Russia has enjoyed some success in Arctic development, particularly when it comes to LNG production. The private company Novatek took the lead by gathering investors (including partners from China and Japan) and expanding the existing Yamal LNG plant, as well as LNG 2 and Ob LNG, the first of which is set to become operational in 2023. State-owned enterprises such as Rosneft and Gazprom, however, have been more reluctant to carry the cost of development in the Arctic. Those companies do not necessarily oppose the Kremlin’s goals in the region, but they have hesitated to invest heavily in the Arctic without

tax breaks or other incentives that could reduce the risk. Earlier this year, Rosneft CEO Igor Sechin asked Russian President Vladimir Putin for $40 billion in tax breaks to pursue the Kremlin’s Arctic goals. The government, however, has countered, offering Rosneft and other companies postponed tax benefits.

Moscow is also tailoring some incentives for individual regional projects. At present, the government is considering providing some financing for the Vostok oil project (with a cost estimated at $156 billion, including support infrastructure) and tax breaks for production at the already active Vankor oil project, which officials will eventually incorporate into Vostok. The considerations suggest that Moscow could decide to offer incentives on a project-by-project basis in the future — although that will also entail long cycles of negotiations and planning before every new stage in Arctic development.

What’s more, both Vostok and Vankor are located onshore, meaning progress in development is likely to slow even further when authorities turn their attention to offshore riches. In deep water, Russia faces not only financial concerns (naturally, the break-even costs offshore are higher) but also technological shortcomings. Russian producers will likely have to partner with Western oil companies that can provide the know-how and technology to operate in such harsh conditions, but the increasing geopolitical tensions between Russia and the West will impede collaboration. For one, while sanctions against Russia’s oil and gas sector might not hurt Russia’s existing production, they could pose a significant hurdle to sufficiently modernizing its energy sector to be able to fully tackle Arctic energy projects.Will Russia’s Ship Come In?

Beyond the energy sector, the government also views Arctic development as a broader move to boost the economy in Russia’s remote regions. Through the development of supporting infrastructure and industry, the Arctic is expected to become a significant driver of economic growth and employment. But mirroring its slow start in exploiting the Arctic’s hydrocarbon resources, shipping along the Northern Sea Route has yet to rise in line with Moscow’s projections. Last year, 18 million metric tons of cargo traversed the Northern Sea Route — most of which was internal Russian traffic among Arctic destinations. Moscow wants to increase this to 80 million metric tons by 2024, but other oil and gas projects like Vostok must materialize at great speed if Russia is to meet this goal.

Activity on the Northern Sea Route has grown over 350 percent from 2013 to 2018, with much related solely to building projects like Novatek’s LNG terminals. Accordingly, as oil and gas facilities come online, the volume of maritime traffic they generate stabilizes, meaning Moscow will require more construction and international transshipment along the North Sea Route if it is to fulfill its aims for shipping.

So while the Kremlin may have goals for the Arctic beyond the energy sector alone, its ambitions still depend almost entirely on energy projects to drum up basic infrastructure development and broader economic activity on the Northern Sea Route. Even disregarding far-reaching offshore projects, the immense financing requirements and political bargaining over state support will inhibit the development even of the easier-to-attain onshore projects. Russia’s Arctic, in the end, will certainly experience increasing economic activity, albeit perhaps not at the rate that Moscow desires — or needs.

Visit our store at http://online.ensemble.net.in

Source: Worldview | Stratfor