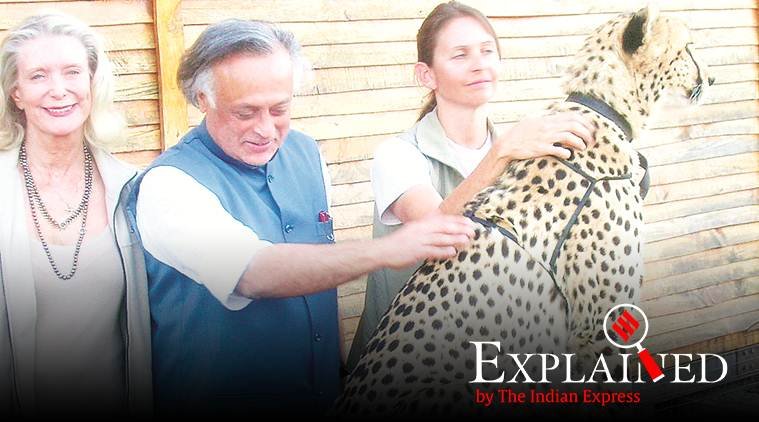

Jairam Ramesh, then Minister of State for Environment and Forests (Independent Charge), at the Cheetah Outreach Centre near Cape Town in April 2010, during a visit to discuss cheetah translocation from South Africa to India. )(PIB/File Photo)

Jairam Ramesh, then Minister of State for Environment and Forests (Independent Charge), at the Cheetah Outreach Centre near Cape Town in April 2010, during a visit to discuss cheetah translocation from South Africa to India. )(PIB/File Photo)

Decades after the cheetah went extinct in India, SC has cleared a proposal for importing a few from Africa. It throws the spotlight on the cheetahs’ future, impact on indigenous species, and translocation of lions.

The Supreme Court’s recent green light to introduction of African cheetahs in a suitable area in India has revived a decade-long debate over the controversial plan first floated in 2009 and shot down by the court in 2013.

To appreciate the cheetah question, one needs to look at the lion parallel. One of the reasons the Supreme Court scrapped the cheetah plan in 2013 was the lopsided focus on flying in an exotic species, as a replacement for what was long gone, at the cost of undermining the future of an indigenous species that is still around.

The dream

The popular appeal of having cheetahs back in the Indian wild was not lost on then Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh who, in 2009, cleared a proposal from Dr M K Ranjitsinh, India’s first director of wildlife during the 1970s, and Dr Y V Jhala, scientist with Wildlife Institute of India, to import a few.

After Iran refused to part with any of its few surviving Asiatic cheetahs, the focus turned to the African variety. At a meeting attended by international experts in September 2009, wildlife geneticist Stephen O’Brien maintained that the Asian and African cheetahs were genetically very similar, and Dr Laurie Marker, head of Namibia-based Cheetah Conservation Fund, offered to help bring in African cheetahs “in stages over the next decade, possibly starting in early 2012”.

By September 2010, India’s cheetah plan was ready and the Centre approved Rs 50 crore for the programme in August 2011.

The brakes

The matter came up before the Supreme Court during a hearing on shifting a few lions from Gujarat to Kuno-Palpur wildlife sanctuary, Madhya Pradesh, which was also one of the sites identified for releasing cheetahs. In May 2012, the court stayed the cheetah plan, and in April 2013, it ordered translocation of lions from Gujarat while quashing the plan for introducing African cheetahs to Kuno-Palpur.

The cheetah plan was revived in 2017 when the government sought permission from the Supreme Court to explore possibilities “in conformity with the applicable law to reintroduce cheetahs from Africa to suitable sites” other than Kuno-Palpur. By then, the lion translocation project was put on the back-burner again.

The design

In April 2013, the Supreme Court had set a six-month deadline for translocating lions from Gujarat to Madhya Pradesh. Between July 2013 and December 2016, the government convened six meetings of the expert committee set up for the lion project. Nothing has moved since.

Instead, the third National Wildlife Action Plan (2017-2031) released in 2017 said that the identification of an alternative home and drawing up a conservation plan for the Asiatic lion will be completed during 2018-2021. Then, Kuno resurfaced as a potential cheetah site in the court.

It is unlikely though that Kuno will get cheetahs. Much of its grasslands that were created by relocating villages have naturally progressed to woodlands not suitable for the African import. While the sanctuary has spotted deer and feral cattle in good numbers, there is barely any presence of the four-horned antelope, chinkara or blackbuck – all potential prey for the cheetah.

With Rajasthan not too keen on cheetahs for Shahgarh in Jaisalmer, and Gujarat’s pitch for Kutch’s Banni grasslands not finding favour, Nauradehi in Madhya Pradesh leads the race to play host to the first batch of imported animals.

The argument

In saving the cheetah, claimed the proponents of the reintroduction plan, one would also save other endangered species of the grassland, such as the endangered Indian wolf and the near-extinct great Indian bustard (GIB). In the umbrella-approach of conservation, multiple species in a forest (tiger reserve, for instance) is protected in the name of a flagship species (i.e. tiger). It is inexplicable, though, as to why one must introduce an exotic replacement for an extinct species to save indigenous species.

Wolves, for example, are the keystone species in Nauradehi and would have to compete with cheetahs. The majestic GIB is a potential prey for the cheetah. In fact, the project excluded Jaisalmer’s Desert National Park because “putting the cheetah in with the bustard cannot be contemplated at all, because of the threat to this most gravely endangered bird”. And yet, it recommended erstwhile GIB habitats for the cheetah, in effect denying the bird any chance of habitat recovery.

The priority

The GIB is not the only species staring down the barrel. The government has identified 20 others – such as the Asian wild buffalo, Jerdon’s courser, red panda and Asiatic lion – that need immediate help to survive. Barring 50 reserves under Project Tiger, all wildlife habitats of the country and the 21 beleaguered species merited a total allocation of Rs 497 crore between 2017-18 and 2019-20. That is Rs 166 crore a year.

A decade ago, the cost of the cheetah project was pegged at Rs 300 crore in the first year alone. In Nauradehi, merely constructing a 150-sq km cheetah enclosure will cost Rs 25-30 crore. To this, compare the recent sanctions of Rs 5 lakh for the Greater adjutant in Gangetic riverine tract in Bhagalpur, Bihar; Rs 1.22 crore for establishing a conservation breeding centre for wild buffaloes in Chhattisgarh; or Rs 3.87 crore for a snow leopard recovery programme in Ladakh.

This raises several questions. Can India’s meagre conservation resources afford to splurge on hosting a few imported animals? Even if the cheetah programme finds an international sponsor, should India’s understaffed and inadequate wildlife management cadre be stretched for a vanity project? Even if a few African cheetahs survive, as they well might inside an enclosure and supplied with prey, what conservation purpose will they serve? And what future will they have once out in the open in a country teeming with people, livestock and feral dogs?

The three-member expert panel will examine these issues in the next four months for the government to reach a considered decision. Meanwhile, as the policy dash for the fastest land animal is being cheered, the lions are running out of time.

Source: Indian Express

For more details : Ensemble IAS Academy Call Us : +91 98115 06926, +91 7042036287

Email: [email protected] Visit us:- https://ensembleias.com/

#cheetah #supremecourt #jairam_ramesh #minister #environment #forests #capetown #translocation #southafrica #diplomatic_edge #foreignpolicy #india #prime_minister #narendra_modi #government #policy #blog #current_affairs #daily_updates #free #editorial #geographyoptional #upsc2020 #ias #k_siddharthasir #ensembleiasacademy