Farmer producers organizations could be a solution to the agrarian distress if they are helped to access credit and markets

One of the reasons for agrarian distress is the declining average size of farm holdings. The average farm size declined from 2.3 hectares (ha) in 1970-71 to 1.08 ha in 2015-16. The share of small and marginal farmers increased from 70 per cent in 1980-81 to 86 per cent in 2015-16. At the state level, the average size of farm holdings in 2015-16 ranged from 3.62 ha in Punjab, 2.73 in Rajasthan and 2.22 in Haryana to 0.75 in Tamil Nadu, 0.73 in Uttar Pradesh, 0.39 in Bihar and 0.18 in Kerala.

To buy our online courses: Click Here

Small farmers face several challenges in getting access to inputs and marketing facilities. A number of innovative institutional models are emerging and there are many opportunities for small and marginal farmers in India. A group or collective is one of the main institutional mechanisms to help the country’s marginal and small farmers.

In the last decade, the Centre has encouraged farmer producer organizations (FPOs) to help farmers. Since 2011, it has intensively promoted FPOs under the Small Farmers’ Agri-Business Consortium (SFAC), NABARD, state governments and NGOs. The membership of an FPO ranges from 100 to over 1,000 farmers. Most of these farmers have small holdings. The ongoing support for FPOs is mainly in the form of, one, a grant of matching equity (cash infusion of up to PRs 10 lakh) to registered FPOs, and two, a credit guarantee cover to lending institutions (maximum guarantee cover 85 per cent of loans not exceeding Rs 100 lakh). India has 5,000 to 7,500 such entities as per different estimates and a majority of them are farmer producer companies. The budget for 2018-19 announced supporting measures for FPOs including a five-year tax exemption while the budget for 2019-20 talked of setting up 10,000 more FPOs in the next five years.

NABARD has undertaken a field study on the benefits of FPOs in Punjab and Madhya Pradesh. The study shows that in nascent FPOs, the proportion of farmer members contributing to FPOs activities is 20-30 per cent while for the emerging and mature FPOs it is higher at about 40-50 per cent.

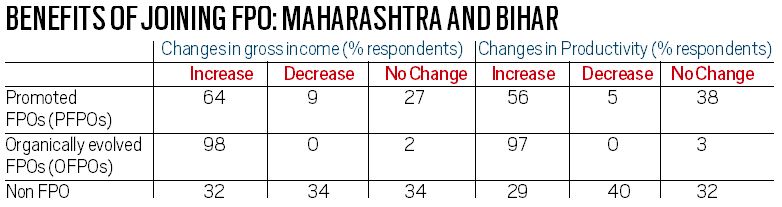

Note: Sample: PFPOs= 303; OFPOs= 99; Non-member=171 Source: Devesh Roy et al, IFPRI, 2020

Note: Sample: PFPOs= 303; OFPOs= 99; Non-member=171 Source: Devesh Roy et al, IFPRI, 2020

Devesh Roy and his co-authors at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) have undertaken a comparative study of FPOs in Maharashtra and Bihar. In Maharashtra, some of the FPOs have organically evolved (OFPOs) when farmers have taken the lead to adopt market-oriented practices, develop cost-effective solutions in production and marketing. In the case of Bihar, almost all FPOs have been promoted (PFPOs). The table shows benefits of FPOs for gross income and productivity.

The survey reveals that 98 per cent of the respondents for OFPOs report an increase in gross income while only 2 per cent indicate decline in the same. For PFPOs, 64 per cent report an increase in gross income while 27 per cent report no change in income. In contrast to these two groups, only 32 per cent of the non-members indicate an increase in gross income. Similar numbers can be seen for productivity. These results show that FPOs are doing better than non-FPO farmers and within FPOs, organically evolved FPOs are more beneficial than pushed or promoted FPOs.

Some studies show that we need more than one lakh FPOs for a large country like India while we currently have less than 10,000. Among other things, we emphasize on three issues for the improvement of FPOs in order to help the small farmers. First, the above issues such as working capital, marketing, infrastructure have to be addressed while scaling up FPOs.

Getting credit is the biggest problem. Banks must have structured products for lending to FPOs. These organizations lack professional management and, therefore, need capacity building. Second, they have to be linked with input companies, technical service providers, marketing/processing companies, retailers etc. They need a lot of data on markets and prices and other information and competency in information technology. Third, FPOs can be used to augment the size of the land by focusing on grouping contiguous tracts of land as far as possible — they should not be a mere grouping of individuals. Women farmers also can be encouraged to group cultivate for getting better returns. FPOs can also encourage consolidation of holdings.

Read More: A voyage to map the Indian ocean genome

To conclude, FPO seems to be an important institutional mechanism to organize small and marginal farmers. Aggregation can overcome the constraint of small size. They can’t compete with large corporate enterprises in bargaining. The real hope is in farmer producer organizations (FPOs) that allow members to negotiate as a group and can help small farmers in both input and output markets. The FPOs have to be encouraged by policy makers and other stakeholders apart from scaling up throughout the country to benefit particularly the small holders.

While small farmers gain greater bargaining power through FPOs in relation to the purchase of inputs, obtaining credit and selling the produce, the fundamental problem of the small size of holdings giving only a limited income is not resolved. While incomes will rise because of the benefits flowing from FPOs, they may not still be adequate to give a reasonable income to small and marginal farmers. That issue has to be handled separately.