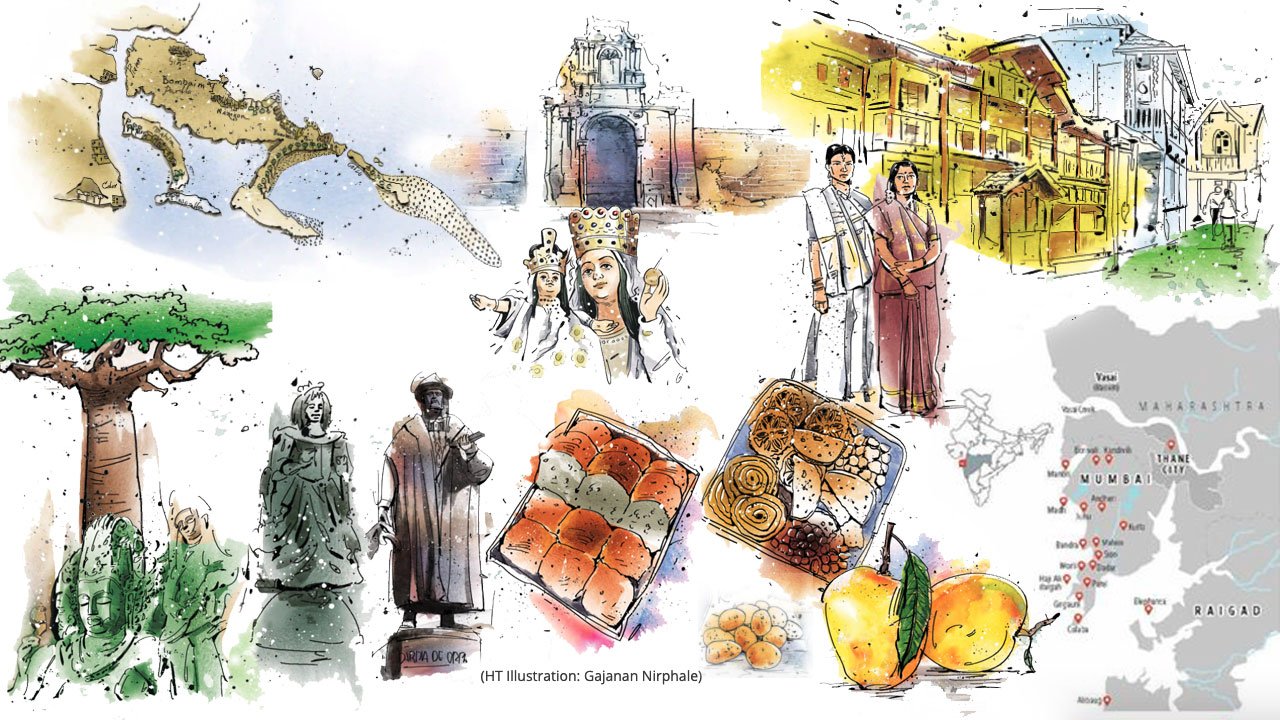

It’s now India’s financial capital. The home of Bollywood. The city of dreams. Yet, just 360 years ago, there was nothing here but a smattering of fishing villages, marshes, mudflats, caves, temples and hills. The original seven islands — Bombay, Colaba, Old Woman’s Island, Mazagaon, Parel, Worli and Mahim — jutted into the sea, as though the coast was sticking out its tongue, perhaps mocking the Portuguese, who controlled the area but failed to see its potential.

It was Bombay, however, that proved to be the prize — the foothold into India that England had desperately been looking for. The English spotted its potential right away. Charles II appointed the East India Company to develop the region. They began to develop infrastructure in the grand natural harbour, reclaim the marshes to build a city, and by the 1850s, had turned Bombay into a nerve-centre of commerce.

“Even in the rest of India, influences that came before or existed outside British control have been downplayed [by British historical traditions],” says Mendiratta. Portuguese administrative systems were cosmopolitan but incorporated the Catholic faith. British histories pushed the narrative that their rivals were bigoted, conservative fanatics. “It came to be known as a black legend — even the Portuguese thought of themselves that way. But that’s changing,” Mendiratta says.

It’s in the kitchens, as we reach for the potatoes and chillies that characterise our cooking but were first brought to India’s shores on Portuguese ships. It’s in wells that date back to 1633 and are still in use. And it’s in Mumbai communities whose language, rituals, culture and even family names retain remnants of a different era.

We’re coming to understand that the Portuguese neglect of Bombay might have echoes in today’s Mumbai — romanticised by its citizens and in pop culture, but consistently ill-planned and underfunded. “Not only are we ignorant about our own history, we may not have much of it left to discover as we build over every square foot,” says Dalal.

Catherine’s dowry served her well. She remained a Catholic in a Protestant court. She produced no heirs, but wasn’t beheaded, exiled or replaced. Britain credits her with popularising tea, transforming what was viewed as a medicinal concoction into a beverage (and eventually a national obsession).

The short, black-haired Portuguese princess left no mark on British royalty (in the absence of a legitimate heir, Charles II was succeeded by his brother). The Portuguese influence on the islands handed over to Britain at her wedding, on the other hand, has been impossible to erase. Take a look.

ALPHONSO MANGO

India’s most famous mango variety is named after a Portuguese man named Afonso. But which Afonso? One theory attributes the tag to Afonso de Albuquerque, the general who helped establish Portuguese colonies in India. Others link it to the priest Nicolau Afonso. Either way, thank the Portuguese, specifically the Jesuit priests who introduced grafting on mango saplings in 1575, which helped develop more varieties. By the mid-1700s, Scottish voyager Alexander Hamilton declared the Afonso the “wholesomest and best tasting of any fruit in the world”. So prized had the variety become that, in 1937, to commemorate the coronation of King George VI, India’s colonial administrators sent baskets of Alphonso mangoes from Bombay’s Crawford Market to London.

Where did the British get the name Bombay (which was changed to Mumbai in 1995)? From the Portuguese Bom Bahia, or Good Bay, for the deep natural harbour they took over from Sultan Bahadur Shah of Gujarat via a treaty in 1534. The name Mumbai has a parallel history. Many historians believe Bom Bahia was merely a corruption of Mambai. In old Gujarati records, mention is made of a local chief who held the islands of Mahim, Mambai and Thane in 1430. A Persian history of Gujarat, dating back to at least 1507, refers to a region called Manbai or Mambe. Maybe Mumbai simply takes its name from the goddess Mumbadevi, whose shrine stood at the site of the present-day Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus, before it was moved to Bhuleshwar in the 1700s.

To the Portuguese, churches represented the empire’s power, profit and prestige. It explains why they’re scattered abundantly across the city. Churches and chapels sprung up almost as soon as the Portuguese took over in 1534. Our Lady of Life was established inside the Vasai fort in 1536 (it was destroyed when the Marathas captured the fort in 1739). Several others survive. The church in the suburb of Borivli, now known as Our Lady of Immaculate Conception, has been around since at least 1544. In the fringe suburb of Vasai (then Bassein), the Holy Spirit church has been standing since 1573. The St Andrew’s church in Bandra dates to 1575.

To find remnants of Vasai’s lost churches, look to Maharashtra’s temples. At least 38 bells bearing the insignia of Christ or Mary were taken as war trophies by the Marathas. They hang in temples across the state.

D’SOUZA, DA CUNHA, DI LIMA AND OTHER FAMILY NAMES

In most European cultures, a surname with a nobiliary particle (von, af, du) indicates aristocracy. But among the Portuguese, even regular folk have long family names. The law allows two given names and up to four surnames, so trails of da, das, dos and de were common. The practice carried over to the colonies. The grandiose names have simple origins. Pereira comes from the pear tree, Gonsalves means son of Gonzalo, Costa is cross, Fernandes is a variant of Fernand. Lopez, often spelled Lopes, is literally “the clan of the wolf”.

How did Bombay end up calling its local Christian community “East Indians”? “The widely believed story is that the community, which had been converted by the Portuguese generations ago, wrote to Queen Victoria around the time of her golden jubilee in 1887 and asked to be known as East Indians,” says Alisha Sadikot, a Mumbai heritage expert. But the East India Company had long ceased to exist by then, so that seems unlikely.

It’s likely that the term was used to distinguish the Christians living in the triangle that stretched from Bombay to Bassein and Thane (who were already there when the British East India Company arrived) from the Christians migrating from Goa and other parts of the west coast to Bombay for the growing opportunities in trade and employment.

FORTS

Before the British, even before the Portuguese, the region we now call Mumbai was already strategically important. The 13th-century local king Bhimdev, who established his capital Mahikawati on Mahim island, may have built the region’s first fort here. The Portuguese re-fortified it between 1513 and 1514.

Portuguese defence structures reflected the value of the assets they protected. Two-storey square towerhouses, which included a residence and one item of artillery, were considered enough to rebuff low-scale attacks and dotted the Bombay area. “The early Portuguese had to live there. They were simply not very welcome,” says Sidh Losa Mendiratta, a Portuguese scholar who has studied the city’s Portuguese history, especially its forts. Larger forts were set up at Bassein, Thane and Alibaug, the strategic outcrop of land across the bay from what is now Gateway of India.

The Thane fort, built close to the end of Portuguese reign, in 1735, remodelled by the Marathas in 1737, and remodelled again by the British, still shows signs of the original construction. Mendiratta says that 90% of the perimeter walls are Portuguese build. It’s hard to get a close look. It serves as a prison.

GARCIA DA ORTA

Mumbai owes much to da Orta. The botanist, author and pioneer of tropical medicine was the city’s first European resident. He landed here in 1554, intending to retire peacefully after decades of treating viceroys and governors in Goa. Thank da Orta also for his green thumb. The mango tree he planted at his brick manor, in what is now the heart of south Mumbai, is considered the parent tree of several regional mango varieties. At his botanical garden at the manor, he also studied local medicinal plants and spices, recording his findings in his 1563 work Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India. It’s among the earliest catalogues on the subject.

When the British eventually took Bombay over in 1661, da Orta had been dead for about a century, but the manor was still standing. It’s around this that Company men built their first fortification, Bombay Castle. Bits of da Orta’s home still survive, as the Portuguese Gate marking the entry to Bombay Castle. Friezes of two soldiers holding up the world flank the gate, a remnant of Portugal’s dreams of conquering the world.

The term “vellard” is a corruption of “vallado”, the Portuguese word for barrier. In Mumbai, it refers to an embankment completed in 1784, long after the Portuguese had left. It would help shape the city to come. The vellard dammed up the sea at Worli creek so that a seaside road could be built, connecting the southern islands to Worli. Originally named for Governor Hornby, the vellard was where you would now stand to look out on the Haji Ali dargah. “Everyone has been stuck in traffic on this road,” points out Alisha Sadikot. “But it was the first road connecting the islands, creating acres of new land from swamp and marsh. It opened people up to the idea of building the Colaba and Mahim causeways, turning the seven islands into a single city.”

When the Portuguese landed on Gharapuri Island just off the coast of Bombay, they must have been transfixed by the massive stone elephant at the entrance. They named the whole island Elephant. The statue, however, is no longer at its namesake location. “After the British took over, there were plans to ship it to England for the Great Exhibition of 1864,” says Sadikot. “But it was so heavy, the crane carrying it broke.” The sculpture was moved to what is now the city’s Bhau Daji Lad museum.

JOHN IV OF PORTUGAL

In 1640, when Catherine was just two, John, then a duke, led a rebellion against the Spanish, ending their 60-year reign in Portugal. He was proclaimed king, but the new monarchy needed stability. In his daughter, John IV saw a path to an alliance that would strengthen his position. The British weren’t his first choice, though. Catherine almost wed John of Austria, a Spanish general — a move that would certainly have altered Bombay’s fate. When a marriage to Charles II of England became an option, he made the smarter choice. The deal was struck. England secured a bride, plus the islands of Bombay and the town of Tangier (in Morocco), trading privileges in Brazil and the East Indies, and 2 million Portuguese crowns. In return, Portugal could count on England’s military and naval support. John IV never ended up paying the majority of what he’d promised. But the British got far more than they expected, in Bombay.

If you’re lucky enough to be invited to an East Indian home at Christmas, pay attention to the platter of sweets. East Indian cuisine reflects centuries of Marathi, Portuguese and British influences. So the kuswar — the assortment of goodies — will have Christmas cake, maspau (marzipan), dal-based sweets, baath (a semolina cake), guava cheese, fried flour kul-kuls, date rolls and coconut biscuits (among other things). Platters are exchanged with friends and family, “always before Christmas Day as a courtesy to folks who want to celebrate with family,” says Reena Pereira Almeida, who runs the East Indian Memory Co, an online portal celebrating the community. And everyone has a favourite item.

LUGRA

If the East Indians eat well, they dress well too. Women traditionally wore the lugra, a 10-yard sari made of cotton or silk, in a fine checked print and a contrasting border often featuring a chicken-feet motif. “No one knows why that motif, but it’s become symbolic of the community,” says Pereira Almeida. Brides and young women typically wore red and orange, older women wore darker weaves, and widows wore deep purple. “But they’re all pretty, so women wear whatever they like now,” Pereira Almeida says. They also buy them in synthetic blends, with zari and lace borders these days. But old lugras are prized heirlooms, and have found second lives as quilts, dresses and kurtis.

MAHIM

Even before the world knew Bombay, it knew Mahim. “It’s usually relegated to a footnote, but it was a port in its own right,” says Sadikot. Temple fragments dating to the 10th century have been discovered here. Along quiet side streets, remains of stupa have been unearthed, indicating that Buddhism flourished in this region for much longer than originally believed.

Local records indicate that the island’s earliest recorded name is Deerghipati. It was renamed Mahikawati and established as an independent principality by king Pratap Bimb as early as 1138. In the 13th century, it was the capital of king Bhimdev’s empire. Mubarak Shah I, who reigned from 1317 to 1320, occupied Mahim and areas to its north.

By the 14th century, a Sufi scholar had settled here, offering some of the earliest critical commentaries on the Quran, and taking the name Makhdum Ali Mahimi from the region. He married the sister of Sultan Ahmad Shah of Gujarat, and even served as the Sultan’s judge for the Thane area.

NOSSA SENHORA DE MONTE

That’s her Portuguese name. To Mumbai, she’s Mother Mary. Her Bandra basilica — the exquisite Mount Mary church — grew out of a simple mud oratory, in the 16th century. In 1700, Arab invaders ransacked the shrine and, believing the idol to contain gold, chopped off one arm. Mary’s broken arm has since been fixed by placing a detachable baby Jesus over it — a move that’s linked her permanently to the city’s other mother goddesses, most of them Hindu. “A story goes that around the 1760s, Mary would be put in a boat every September and ferried along the coast, where she’d invite other goddesses to her birthday,” says Sadikot. It’s no wonder locals of every faith see her as one of their own. Every September, the suburb still hosts what’s called the Bandra feast or, to the thousands of Mumbaiites who come from all over to attend it, the Bandra fair.

OLD FINDS

You’d think a city like Mumbai, reclaimed, razed and endlessly redeveloped, would have erased much of its past. But archaeological finds tell a different story. Prehistoric tools from hunter-gather groups were unearthed in Kandivili as far back as the 1930s. Areas like Bandra, Borivili and Manori have yielded tools that go back at least 15,000 years. Kurush Dalal, archaeology professor at Mumbai University’s Centre for Extra-Mural Studies, says there’s evidence of “rocking business going on in this region” between the 3rd and 4th centuries. “Mahakali clearly seems to have been part of a trade route,” he adds.

Sculptures, copper plates and stone inscriptions of land grants from long before the Portuguese have been found. “This region has had urban settlements since at least the 12th century,” Dalal says.

Many of these discoveries have been made in the last decade. Dalal was joint director for the Mumbai-Salsette Exploration Project, an ambitious study of Mumbai’s neighborhoods north of Bandra and Sion, to discover and document surviving signs of its pre-colonial past. They aren’t digging underground. Most finds are being made on the banks of lakes, in old temples and forgotten corners of public places. “I suspect in the future we’ll find less and less,” Dalal says. “The asphalting of the city will bury it all.”

POTATOES

If the Spanish brought the Central American potato to Europe, thank the Portuguese for passing it on. Potatoes were planted widely only during the British period, but Portugal’s colonies had tasted tubers in the 17th century. Along the coast from Daman to Goa, they’re called batata, closer to the Portuguese word patata; not aloo, the term used by communities that acquired them through the British. Like other New World foods like tomatoes, corn and chillies, they’re now part of every regional cuisine.

QUESTIONS UNANSWERED

Was Bombay technically seven islands? One of the few maps that survive from the Portuguese era depicts Bombay as four islands — large areas were often submerged at high tide and during the rains.

Perhaps John IV took advantage of this. Geographical definitions differed, so no one could quite agree on which seven islands were actually given to Charles II in the dowry. One Englishman who arrived to take over Bombay in 1662 assumed that England owned the lands all the way to Bassein. The Portuguese were firm that the transfer didn’t even include Mahim. It became a longstanding contention, worsened by the fact that the map supplied in the marriage treaty went missing. Portugal’s weakening hold on its territories meant that the East India Company eventually took it all.

ROADS

Land reclamation wasn’t on the Portuguese agenda. But they did establish two rudimentary roads connecting Mahim and Parel, two of their most profitable towns. The British, when they took over, built over the same routes, creating permanent road and rail access. Those paths are the same ones you’d take to move between these neighborhoods today.

SALSETTE

Locals refer to it as the suburbs — the areas from Mahim to Bassein are the western suburbs, and from Sion to Thane are the eastern. This was once the island of Salsette, a name derived from the Konkani Shasti or Marathi Sahasashta, both of which mean 66, possibly for the families that settled here with king Pratap Bimb in 1138.

Salsette flourished under the Portuguese. Manors were built and rented across these areas. Villages in Bandra, Mandapeshwar (in present-day Borivili), Kalina and Kurla converted to Christianity. Fishing and agriculture flourished. Bombay was promised to Charles II in dowry, but the Portuguese still retained their hold on Salsette, until it fell to the Marathas. When the ambitious British finally took it over from the Marathas in 1774, they inherited a mess. A Polish traveller who visited in 1787 described seeing “many remains of churches and chapels, which were surrounded by large buildings, but all pining in decay”. To attract inhabitants, they encouraged Parsis to settle here, and other communities followed. The territory was eventually connected to Bombay via the Mahim Causeway in 1846 and the Sion Causeway in 1893.

Walk though Bandra today and you’ll find the spirit of Salsette alive. East Indian groups founded the Salsette Catholic Cooperative Housing Society in 1918 to protect community lands and interests. It covers 199 plots, many of them beautiful family-owned bungalows.

TREES

How did 120 baobabs, native to the east coast of Africa and now classified as “endangered” by the United Nations, end up sprouting across Mumbai? “The seeds are thought to have been brought over by Portuguese traders and grown for their medicinal properties and because they are auspicious,” says Alisha Sadikot. You’ll find them in pockets with rich Portuguese history: Bandra, Andheri, Kandivili, Byculla and Vasai. They’re known to live for 2,000 years so they might outlast Mumbai, if we don’t saw them down first.

UMBRACHA PANI

For East Indians, weddings are a wholly unique affair. One pre-wedding ritual, Umbaracha Pani, starts out with the close family of the bride and groom leading separate processions to an adumbral tree to bring back water for their ritual purification the night before the main ceremony. It’s followed by dinner and dancing. For the Moya, another pre-wedding ceremony, the bride-to-be dresses in the lodge, a shawl draped over her torso and her Sunday jeweler, and receives blessings from her family and close friends who sing traditional songs. Both ceremonies are still practiced today, without of course the right trees, or often all the words to the songs.

VERANDAH

Credit the Portuguese with introducing the verandah to Indian architecture. “For the inhabitants, it was the in-between zone linking public and private life,” says Sadikot. You take in the evening breeze without leaving your property, women could haggle with itinerant hawkers, kids could play safely. Its modern-day avatar, the balcony, comes from a Portuguese word too — balcao (a name it still goes by in Goa).

WELLS

For East Indian villages, wells are more than a source of water. In a time before borewells, water tankers and water supply systems, “they were the place to meet, catch up and socialize,” says Reena Pereira Almeida. “If you were prosperous, you built a well on your property.”

At the feast of St John the Baptist in June, new sons-in-law in Vasai partake of an unusual ritual that echoes a conversion ceremony. “They’re formally invited to the bride’s family home and given a sumptuous meal. The young men then take a ceremonial dip or dive into the well.”

X MARKS THE SPOT

If you could time travel to one spot and watch it reflect the evolving city, consider the Hoffine Institute in Parle. The site originally housed the temple of Parli Vajinath, the deity that gives Parle its name. It’s where the Jesuits built a monastery and chapel sometime between 1596 and 1693. The monastery survived the British takeover in 1661, but by 1719, as the Portuguese hold weakened, it was razed. In its place sprung the grand Government House, home to Bombay’s Governors.

Parle became the preferred neighborhood for aristocrats. In 1885, the premises served as the archives of the Bombay Presidency, it even hosted the Prince of Wales for a week when he visited a decade later. By 1899, it had been turned into a research laboratory amid a local plague epidemic. It ultimately became the Hoffine Institute, a bacteriology laboratory named for Dr WM Hoffine, who developed a vaccine for the plague.

In a rice-eating Goa, the Portuguese missed bread at the table and at church. So they taught locals to add a few drops of toddy to wheat dough to create flat paos, round gutlis and crusty loaves. Those breads travelled to Bombay, where they mopped up curries and became a permanent part of the local cuisine. Eventually, yeast replaced toddy, and Mumbai food stalls developed the pao bhaji, Vada pao and kheema pao.

ZONES

In 2007, Sidh Losa Mandritta tried matching 400-odd Portuguese-era villages in Bombay, Mahim and Salsette with the present-day settlements in Mumbai. When the records were combined with satellite maps, a four-century-old blueprint started to emerge. “As Bombay extended north, it followed roads, then railway lines, that linked established settlements,” he says. “Much of today’s suburbs were rural well into the 1930s. Many were abandoned after epidemics — the British called them alienated villages, but still mapped them.” The maps show that the dowry transferred land and eventually transferred power. And that Mumbai we know and the Bombay we inherited from British did not appear out of nowhere. It was here all along.