Re-imagining India and Africa

Delhi’s Strategy for Indo-Pacific needs to recognise the importance of the continent

Although scepticism about the idea of Indo-Pacific endures, the new geopolitical construct continues to gain ground. In embracing the concept late last month, the Association of South East Asian Nations has taken a big step towards bridging the eastern Indian Ocean with the Pacific. If South East Asia has been central to the Indo-Pacific debate, Africa remains a neglected element.

The ASEAN’s Indo-Pacific vision has come after a prolonged internal debate among its ten member states. The initiative came from Indonesia — the largest member of the ASEAN and an early champion of the Indo-Pacific. After all, Indonesia is the land link between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Almost all the maritime traffic between the two oceans passes through the narrow straits formed by the Indonesian archipelago.

As in India, so in the ASEAN, there was much initial suspicion about the meaning of and the motivations behind the term Indo-Pacific. If India’s preferred focus was on the Indian Ocean, the ASEAN had grown accustomed to the idea of the Asia-Pacific. If the UPA government was deeply divided on the notion of the Indo-Pacific, many in the ASEAN saw little reason to replace Asia-Pacific with Indo-Pacific.

The Modi government, which has shed so many hesitations of the UPA era, eventually adopted the Indo-Pacific framework. In the east, Indonesia’s initiative is an important landmark in the way South East Asia rethinks its geography. Delhi and Jakarta are also well-placed to recognise the growing importance of Africa for the security and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific.

Delhi and Jakarta remember that the 1955 Bandung Conference was not just about Asia or non-alignment, but promoting Afro-Asian solidarity. India and Indonesia can’t forget Africa’s role in shaping the outcome of the World War II in Asia. Nearly 1,00,000 African soldiers participated in the war to liberate Burma and South East Asia from Japanese occupation.

Today, the rise of Asia and Africa is beginning to reconstitute the geographies of the eastern hemisphere and break down the artificial mental maps that emerged in the 20th century between different sub-regions of the Indo-Pacific, stretching from Africa to the Western Pacific.

If Europe and North America dominated Africa’s economic relationship in the past, China, India, Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN share the honours today with the US and EU. China, Japan, Korea and India are also major investors in Africa as well as providers of development assistance.

China and Japan are also playing a major role in the modernisation and expansion of infrastructure in Africa. China certainly has strong reservations about the Indo-Pacific terminology; but no one is doing more to integrate the two oceans than Beijing. China’s maritime silk road is about connecting China’s eastern seaboard with the Indian Ocean littoral. According to publicly available information analysed by the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, China is involved in the development of 47 ports in sub-saharan Africa. African energy and mineral resources and the sea lines of communication bringing them to China are now seen as vital lifelines in Beijing.

Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, who reinvented the Indo-Pacific has also underlined the importance of connecting Africa to Asia through growth corridors. If the dynamic economic interaction between the “two continents and two seas” in Abe’s words) has been widely noted, the increasing strategic nexus between the eastern and western ends of the Indo-Pacific has not drawn adequate attention.

Consider for example, China’s expanding defence and security engagement in Africa. Over the last few years, China has emerged as the largest major arms supplier to Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, China accounted for nearly 27 per cent of all arms imports by Sub-Saharan Africa during 2013-17. China is a major champion of peacekeeping in Africa, not in manpower contribution that is dominated by Subcontinent, but in financial, material, logistical and institutional support.

China is ramping up its support for internal security structures, including national law enforcement and police organisations, in Africa. In 2017, Beijing established its first foreign military base in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa. And China is not the only one.

Japanhas run a small military facility in Djibouti since 2011. This is Japan’s first foreign base since the Second World War. South Korea, following a similar track, stationed about 150 troops in the UAE for African military missions, including peacekeeping.

China, Japan and Korea had all come to the region in the late 2000s on anti-piracy missions. As piracy declined, they have found it necessary to stay on amidst what is now being called the “new scramble for Africa”. Former colonial powers like France and Britain are no longer taking their position in Africa for granted and are recasting their military act in the western edge of the Indo-Pacific.

The US, which was focused on terrorism and other non-military threats after 9/11, is paying attention to Africa’s new geopolitics. Russia, which seemed to turn its back on Africa after the collapse of the Soviet Union, is now returning with some vigour. Meanwhile, many regional actors like Iran, UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey are taking growing interest in African security affairs.

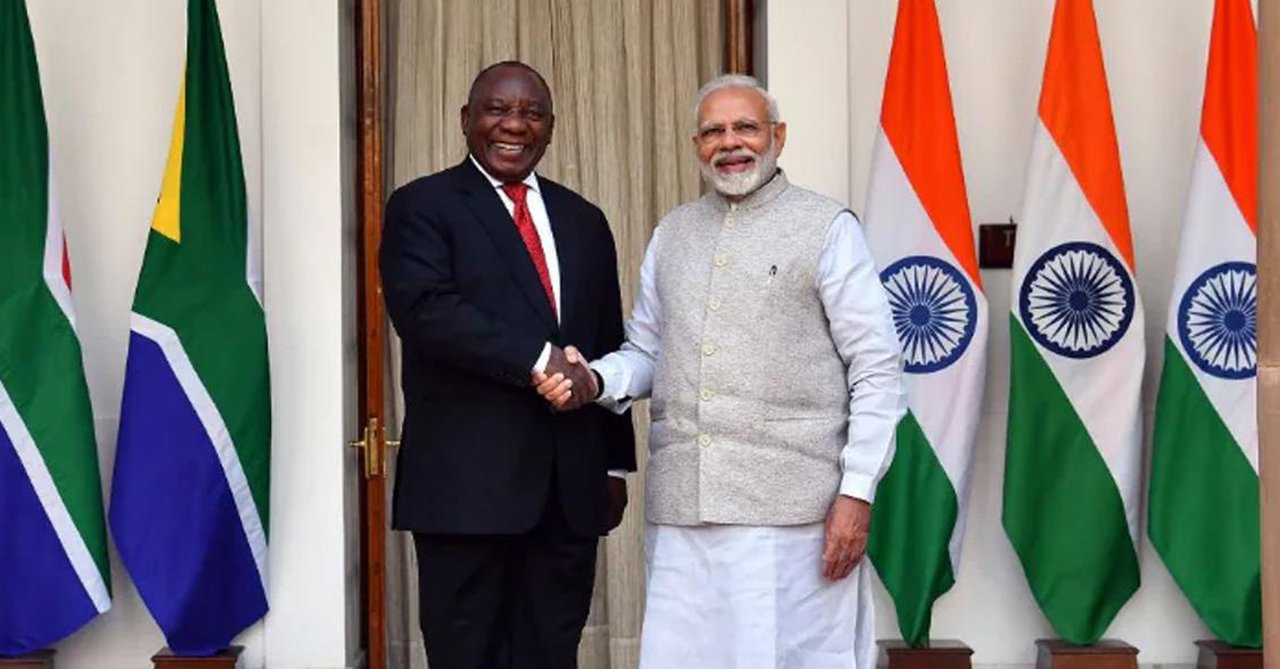

During his first term, Prime Minister Narendra Modi elevated the engagement with Africa by hosting a summit in Delhi for all the African leaders, unveiling sustained high level political contact, expanding India’s diplomatic footprint, strengthening economic engagement and boosting military diplomacy. But the scale and speed of Africa’s current transformation means the PM has his African tasks cut out in the second term.

AFRICA?

Today, the rise of Asia and Africa is beginning to reconstitute the geographies of the eastern hemisphere and break down the artificial mental maps that emerged in the 20th century between different sub-regions of the Indo-Pacific, stretching from Africa to the Western Pacific.

If Europe and North America dominated Africa’s economic relationship in the past, China, India, Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN share the honours today with the US and EU. China, Japan, Korea and India are also major investors in Africa as well as providers of development assistance.

China and Japan are also playing a major role in the modernisation and expansion of infrastructure in Africa. China certainly has strong reservations about the Indo-Pacific terminology; but no one is doing more to integrate the two oceans than Beijing. China’s maritime silk road is about connecting China’s eastern seaboard with the Indian Ocean littoral. According to publicly available information analysed by the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, China is involved in the development of 47 ports in sub-saharan Africa. African energy and mineral resources and the sea lines of communication bringing them to China are now seen as vital lifelines in Beijing.

Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, who reinvented the Indo-Pacific has also underlined the importance of connecting Africa to Asia through growth corridors. If the dynamic economic interaction between the “two continents and two seas” in Abe’s words) has been widely noted, the increasing strategic nexus between the eastern and western ends of the Indo-Pacific has not drawn adequate attention.

Consider for example, China’s expanding defence and security engagement in Africa. Over the last few years, China has emerged as the largest major arms supplier to Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, China accounted for nearly 27 per cent of all arms imports by Sub-Saharan Africa during 2013-17. China is a major champion of peacekeeping in Africa, not in manpower contribution that is dominated by Subcontinent, but in financial, material, logistical and institutional support.

China is ramping up its support for internal security structures, including national law enforcement and police organisations, in Africa. In 2017, Beijing established its first foreign military base in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa. And China is not the only one.

Japan has run a small military facility in Djibouti since 2011. This is Japan’s first foreign base since the Second World War. South Korea, following a similar track, stationed about 150 troops in the UAE for African military missions, including peacekeeping.

China, Japan and Korea had all come to the region in the late 2000s on anti-piracy missions. As piracy declined, they have found it necessary to stay on amidst what is now being called the “new scramble for Africa”. Former colonial powers like France and Britain are no longer taking their position in Africa for granted and are recasting their military act in the western edge of the Indo-Pacific.

The US, which was focused on terrorism and other non-military threats after 9/11, is paying attention to Africa’s new geopolitics. Russia, which seemed to turn its back on Africa after the collapse of the Soviet Union, is now returning with some vigour. Meanwhile, many regional actors like Iran, UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey are taking growing interest in African security affairs.

During his first term, Prime Minister Narendra Modi elevated the engagement with Africa by hosting a summit in Delhi for all the African leaders, unveiling sustained high level political contact, expanding India’s diplomatic footprint, strengthening economic engagement and boosting military diplomacy. But the scale and speed of Africa’s current transformation means the PM has his African tasks cut out in the second term.

Re-imagining India and Africa

Delhi’s Strategy for Indo-Pacific needs to recognise the importance of the continent

Although skepticism about the idea of Indo-Pacific endures, the new geopolitical construct continues to gain ground. In embracing the concept late last month, the Association of South East Asian Nations has taken a big step towards bridging the eastern Indian Ocean with the Pacific. If South East Asia has been central to the Indo-Pacific debate, Africa remains a neglected element.

The ASEAN’s Indo-Pacific vision has come after a prolonged internal debate among its ten member states. The initiative came from Indonesia — the largest member of the ASEAN and an early champion of the Indo-Pacific. After all, Indonesia is the land link between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Almost all the maritime traffic between the two oceans passes through the narrow straits formed by the Indonesian archipelago.

As in India, so in the ASEAN, there was much initial suspicion about the meaning of and the motivations behind the term Indo-Pacific. If India’s preferred focus was on the Indian Ocean, the ASEAN had grown accustomed to the idea of the Asia-Pacific. If the UPA government was deeply divided on the notion of the Indo-Pacific, many in the ASEAN saw little reason to replace Asia-Pacific with Indo-Pacific.

The Modi government, which has shed so many hesitations of the UPA era, eventually adopted the Indo-Pacific framework. In the east, Indonesia’s initiative is an important landmark in the way South East Asia rethinks its geography. Delhi and Jakarta are also well-placed to recognize the growing importance of Africa for the security and prosperity of the Indo-Pacific.

Delhi and Jakarta remember that the 1955 Bandung Conference was not just about Asia or non-alignment, but promoting Afro-Asian solidarity. India and Indonesia can’t forget Africa’s role in shaping the outcome of the World War II in Asia. Nearly 1,00,000 African soldiers participated in the war to liberate Burma and South East Asia from Japanese occupation.

Today, the rise of Asia and Africa is beginning to reconstitute the geographies of the eastern hemisphere and break down the artificial mental maps that emerged in the 20th century between different sub-regions of the Indo-Pacific, stretching from Africa to the Western Pacific.

If Europe and North America dominated Africa’s economic relationship in the past, China, India, Japan, South Korea and the ASEAN share the honours today with the US and EU. China, Japan, Korea and India are also major investors in Africa as well as providers of development assistance.

China and Japan are also playing a major role in the modernization and expansion of infrastructure in Africa. China certainly has strong reservations about the Indo-Pacific terminology; but no one is doing more to integrate the two oceans than Beijing. China’s maritime silk road is about connecting China’s eastern seaboard with the Indian Ocean littoral. According to publicly available information analyzed by the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, China is involved in the development of 47 ports in sub-Saharan Africa. African energy and mineral resources and the sea lines of communication bringing them to China are now seen as vital lifelines in Beijing.

Japan’s prime minister, Shinzo Abe, who reinvented the Indo-Pacific has also underlined the importance of connecting Africa to Asia through growth corridors. If the dynamic economic interaction between the “two continents and two seas” in Abe’s words) has been widely noted, the increasing strategic nexus between the eastern and western ends of the Indo-Pacific has not drawn adequate attention.

Consider for example, China’s expanding defence and security engagement in Africa. Over the last few years, China has emerged as the largest major arms supplier to Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, China accounted for nearly 27 per cent of all arms imports by Sub-Saharan Africa during 2013-17. China is a major champion of peacekeeping in Africa, not in manpower contribution that is dominated by Subcontinent, but in financial, material, logistical and institutional support.

China is ramping up its support for internal security structures, including national law enforcement and police organizations, in Africa. In 2017, Beijing established its first foreign military base in Djibouti in the Horn of Africa. And China is not the only one.

Japan has run a small military facility in Djibouti since 2011. This is Japan’s first foreign base since the Second World War. South Korea, following a similar track, stationed about 150 troops in the UAE for African military missions, including peacekeeping.

China, Japan and Korea had all come to the region in the late 2000s on anti-piracy missions. As piracy declined, they have found it necessary to stay on amidst what is now being called the “new scramble for Africa”. Former colonial powers like France and Britain are no longer taking their position in Africa for granted and are recasting their military act in the western edge of the Indo-Pacific.

The US, which was focused on terrorism and other non-military threats after 9/11, is paying attention to Africa’s new geopolitics. Russia, which seemed to turn its back on Africa after the collapse of the Soviet Union, is now returning with some vigor. Meanwhile, many regional actors like Iran, UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Turkey are taking growing interest in African security affairs.

During his first term, Prime Minister Narendra Modi elevated the engagement with Africa by hosting a summit in Delhi for all the African leaders, unveiling sustained high level political contact, expanding India’s diplomatic footprint, strengthening economic engagement and boosting military diplomacy. But the scale and speed of Africa’s current transformation means the PM has his African tasks cut out in the second term.