The Southern Ocean

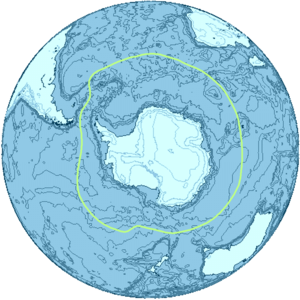

The newly named Southern Ocean off the coast of Antarctica

To buy our online courses: Click Here

- The Southern Ocean, the body of water that surrounds Antarctica is now officially the fifth ocean. Antarctica is defined as all of the land and ice shelves south of 60°S latitude, on the South Pole. It encircles Antarctica.

- National Geographic that started making maps in 1915 had recognized four oceans: the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Arctic Oceans. Starting on June 8 they recognized the Southern Ocean as the world’s fifth ocean. June 8 is also World Oceans Day.

- The Southern Ocean is unlike any other. Scientists say that the glaciers are bluer, the air colder, the mountains more intimidating, and the landscapes more attractive than anywhere else on earth.

- “The Southern Ocean has long been accepted by scientists but was never officially recognized due to lack of agreement internationally”, said National Geographic Society Geographer Alex Tait.

- One of the biggest impacts would be on education, he said: “Students learn information about the ocean world through what oceans you’re studying. If you don’t include the Southern Ocean, then you don’t learn the specifics of it and how important it is.”

- The Southern Ocean is warming up fast due to global warming. Legally modifying the name of the waterbody should help raise attention to these challenges.

Oceanography

- Oceanography is the study of the physical, chemical, and biological features of the ocean. This includes the ocean’s ancient history, its current condition, and its future.

- We use the sea for transportation, food, energy, water, and much more. The oceans are threatened by climate change, pollution, coastline erosion, and the risk of extinction of entire species.

- 70 % of Earth’s surface is covered by water and almost 97 % of that water is saltwater found in the world’s ocean. The sheer size of the ocean and the rapid advancements in technology makes sure that much remains to be discovered.

Biological oceanography

- Biological oceanographers study the ocean’s plants and animals and how they interact with their oceanic environment.

- Humans tend to settle along the world’s 440,000 km of coastline. Local governments spend billions to study and rectify coastal pollution and waste disposal that humans dispose of at sea. The percentage of people living on the coast will remain constant but numbers will increase since the population continues to rise.

- Mountains, valleys, volcanoes, islands, plains, and canyons all exist in similar forms in the ocean too. Earth’s largest continuous mountain chain is the Mid-Ocean Ridge that stretches for over 65,000 km and rises above the water in a few places, like Iceland. Active deep-sea volcanoes supply rich mineral deposits and new rock formations to the seafloor.

- Using remote sensing technology to map the ridges and valleys, Geological Oceanographers study the formations, composition, and history of the seafloor. They analyze its physical characteristics and chemical characteristics to learn how they affect our environment.

- We have learned that natural coastal processes such as rising sea levels, erosion, and storm-related events such as flooding and inland erosion have made our coastal areas unsafe. We try and protect our shores with structures situated along the coast, such as barrier beaches, that are temporary.

- Coastal geologists and coastal engineers, working with oceanographers form policies to minimize damage.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC)

- The other oceans are named after the continents that surround them while the Southern Ocean is defined by a current.

- The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is an ocean current that flows clockwise. When seen from the South Pole the ACC moves from the west to east around Antarctica. This is why the ACC is also known as the West Wind Drift

- The current is circumpolar (it moves around one of the earth’s poles). This happens since no landmass connects with Antarctica. The cold water circling keeps warm ocean waters away from Antarctica which is why the continent can maintain its enormous ice sheet.

- Inside the ACC, the waters are colder and slightly less salty than ocean waters to its north.

- The ACC is familiar to sailors for centuries. It speeds up any travel from west to east but makes sailing extremely difficult in the opposite direction. This is due to the westerly winds.

Svendrups

- The ACC is the powerful circulation feature of the Southern Ocean and has an average transport estimated at 100–150 Sverdrups (Sv, million m3/s) or possibly even higher that makes it the largest ocean current.

- In oceanography, the sverdrup (symbol: Sv) is a metric unit of flow, with 1 Sv equal to 1 million cubic meters per second. Named after Harald Sverdrup, it is used almost only in oceanography to measure the rate of transport of ocean currents.

- In the context of ocean currents, a volume of one million cubic meters may be imagined as a “slice” of the ocean with dimensions 1 km × 1 km × 1 m (width × length × thickness). Thus, a hypothetical current 50 km wide, 500 m (0.5 km) deep, and moving at 2 m/s would be transporting 50 Sv of water.

- The Antarctic Circumpolar Current, at approximately 125 Sv, is the largest ocean current. The entire global input of fresh water from rivers to the ocean is only around 1.2 Sv

Sub Antarctic Zone and Upwelling

- The sub-Antarctic zone is a region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This zone lies at a latitude of between 46° and 60° south of the Equator. Associated with the Circumpolar Current is the Antarctic Convergence. Cold Antarctic waters meet the warmer waters of the subantarctic, creating an area rich in upwelling nutrients.

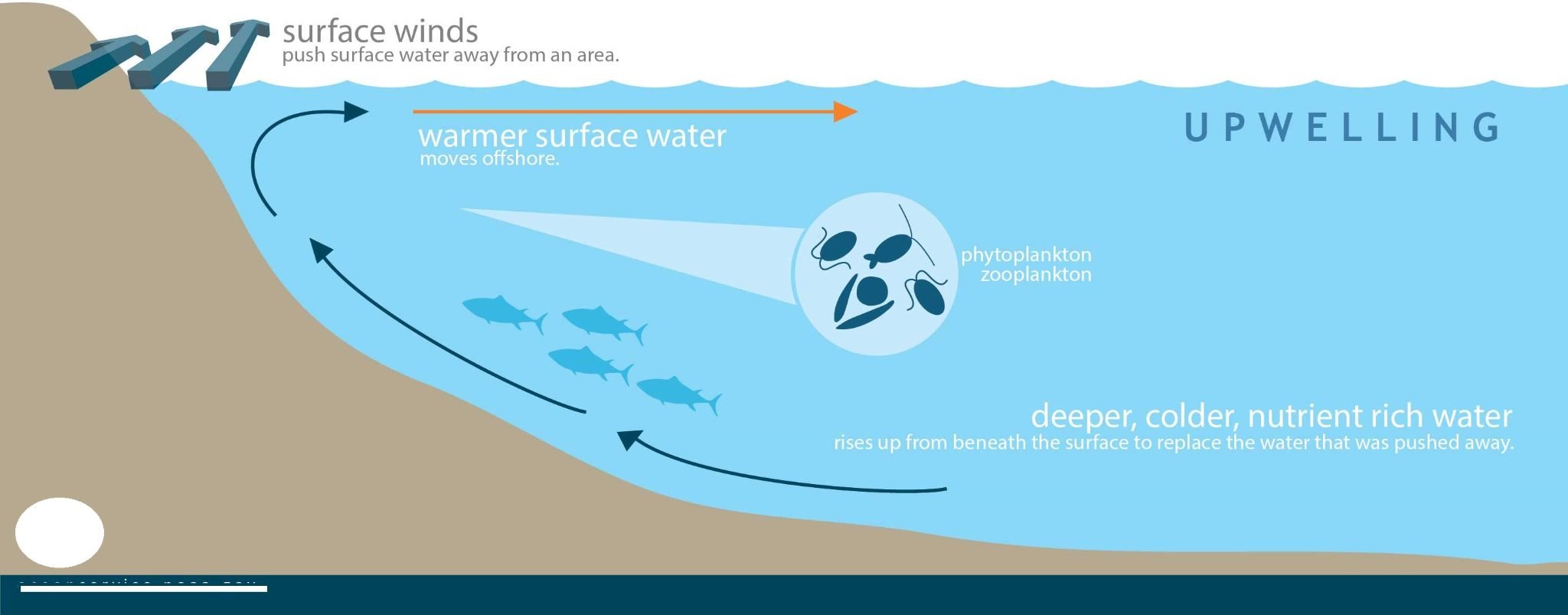

- Winds blowing across the ocean surface push water away. Water then rises up from beneath the surface to replace the water that was pushed away and the process is called “upwelling.”

- The circumpolar current merges the waters of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans and carries up to 150 times the volume of water flowing in all of the rivers.

- Any damage on the cold-water corals nourished by the current will have a long-lasting effect on climate around the world and on different species and forms of life that live underwater

Upwelling

Foodchain (Phytoplankton → zooplankton → predatory zooplankton → predatory fish)

- Plankton is small organisms found in water that move with the ocean currents. Phytoplankton is the self-feeding component of the plankton community and a key part of the ocean and marine ecosystems.

- Like trees and other plants on land, Phytoplankton obtains energy through photosynthesis. They must have light from the sun, so they live in the well-lit surface layers of the oceans. When compared to plants that live on land, phytoplankton is spread over a larger surface area and grows faster than trees (days versus decades).

- Water that rises to the surface as a result of upwelling is typically colder and is rich in nutrients that “fertilize” surface waters.

- These nutrients feed high levels of phytoplankton that then feed copepods and krill which further support food chains including fish, whales, seals, penguins, albatrosses, and a host of other species. This is why good fishing grounds are found where upwelling is common.

- Phytoplankton accounts for about half of all photosynthetic activity on Earth. During photosynthesis, they absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen. The downside is that climate variations kill them rapidly.

The Carbon Sink

- A carbon sink is any reservoir, natural or otherwise, that accumulates and stores some carbon-containing chemical compound for endless periods. This lowers the carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere. Globally, the two most important carbon sinks are vegetation and the ocean

- The leaves of the plants have tiny pores known as stomata. During photosynthesis, green plants absorb carbon dioxide from the air. The carbon dioxide enters the leaves of the plant through the stomata present on their surface.

- Higher concentrations of carbon dioxide make plants more productive because photosynthesis uses the sun’s energy to produce sugar out of carbon dioxide and water. Plants then use sugar as an energy source and as the basic building block for their growth

- Antarctic phytoplankton act as a carbon sink. Areas of open water left from ice melt are good areas for phytoplankton blooms (the birth/development of new phytoplankton). The phytoplankton absorbs carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis. As the blooms die and sink, the carbon can be stored in sediments for thousands of years at the bottom of the ocean.

- This natural carbon sink is estimated to remove 3.5 million tonnes from the ocean each year. 3.5 million tonnes of carbon taken from the ocean and atmosphere is equivalent to 12.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Copepods and Krill

- Zooplankton means animals, small marine creatures that feed on phytoplankton and then become food for fish and other larger species. Tiny zooplankton called “copepods” are like cows of the sea that feed on phytoplankton and convert the sun’s energy into food.

- Copepods vary considerably, but can typically be 1 to 2 mm, with a teardrop-shaped body and large antennae. They absorb oxygen directly into their bodies. Copepods are some of the most abundant animals on the planet

- The crustaceans group includes commonly eaten seafood like shrimp, crab and lobster, prawns, and more importantly Krill. The name, crustaceans, refers to their hard crusts or shells. Krill are small crustaceans and are found in all oceans. It feeds directly on phytoplankton

- Antarctic krill is a species of krill found mainly in the Antarctic waters of the Southern Ocean. It is the dominant animal species on Earth. These small, swimming krill live in large groups (called swarms) that sometimes reach from 10,000 to 30,000 individual animals per cubic meter.

- It grows to a length of 6 centimeters (2.4 in), weighs up to 2 grams, and lives for up to six years. It is a key species in the Antarctic ecosystem and is one of the most abundant animal species on the planet (approximately 500 million tons, between 300 to 400 trillion individuals)

- In the Southern Ocean, the Antarctic krill, makes up estimated biomass (biomass is the mass of living biological organisms in a given area or ecosystem at a given time) of around 379,000,000 tonnes, making it among the species with the largest total biomass. Over half of this biomass is eaten by whales, seals, penguins, squid, and fish each year.

- The Antarctic krill migrate, they move up to the uppermost part of the sea at night and return to the bottom of the oceans during the day. The greatest migration in the world in terms of biomass.

- They thus provide food for predators near the surface at night and in deeper waters during the day.

- Krill are the main prey of fish both big and small, including the blue whale. They feed on phytoplankton and (to a lesser extent) zooplankton and are the main source of food for many larger animals.

Krill

Geopolitics in Antarctica

- Since 1908 seven nations have made formal claims to parts of Antarctica. During the 1940s and 1950s, these competing claims led to diplomatic disputes and even armed clashes.

- In 1948, Argentinean military forces fired on British troops in an area claimed by both countries. The ‘scramble’ for Antarctica intensified in the 1950s.

- By the end of 1955, many countries had created over 20 bases in the Antarctic Peninsula, including Argentina, Chile, Britain, and the United States of America.

- Currently, six major nations of the Southern hemisphere are involved in the Antarctic. Each of these nations – Argentina, Australia, Chile, India, New Zealand, and South Africa – claims a ‘natural’ interest in the future of the polar continent.

Also Read: The National Doctor’s Day 2021

The Antarctic treaty of 1961

- The Antarctic Treaty is set within the Cold War context, a time when the USA and the Soviet Union were involved in a standoff involving nuclear weapons. The USSR began to show interest in Antarctica and there were fears that Antarctica could get entangled in the Cold War. Diplomats designed a treaty setting Antarctica aside as a military-free zone and prevented future territorial claims.

- In the interests of all mankind, it was decided that Antarctica should continue forever to be used exclusively for peaceful purposes. This was to prevent it from becoming the scene of international disputes.

- The twelve countries that had significant interests in Antarctica at the time were: Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Chile, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These countries had established over 55 Antarctic stations in Antarctica.

- The treaty was signed by these 12 nations. The Antarctic Treaty came into effect on June 23, 1961, and now forms the basis of all policies and management in Antarctica. The treaty was the first arms control agreement established during the Cold War.

- It now has 54 nations and the provisions apply to areas south of 60° South Latitude, including all ice shelves.

- The treaty sets aside Antarctica as a scientific preserve, establishes freedom of scientific investigation, and bans military activity on the continent. Since September 2004, the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat headquarters is located in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Antarctica is designated as a continent of peace and cooperation.

Commercial fishing in the Southern Ocean

- The Southern Ocean off Antarctica accounts for 10% of the world’s ocean and is home to thousands of species found nowhere else, from colossal squid and fish with antifreeze proteins in their blood, to bioluminescent worms and brilliantly hued starfish.

- It is also home to millions of predators, including penguins, seals, and whales that depend on large swarms of Antarctic krill that form the base of a fragile food chain.

- By the 1980s, a growing fleet of vessels around Antarctica started catching krill, which are used to make omega-3 supplements, as aquaculture feed, and as fishing bait.

- Chilean sea bass is a high-quality fish that comes from the shores of Chile. A white and flaky fish that tastes similar to cod, when properly cooked, it has a smooth and buttery feel and taste.

- It contains high amounts of Vitamin D, is a rich source of protein, and has plenty of Omega-3 Fatty acids.

- The Patagonian toothfish is a species found in cold waters (1–4 °C) between depths of 45 and 3,850 m (150 and 12,630 ft) found mostly in the Southern Ocean around Subantarctic islands.

- A close relative, the Antarctic toothfish, is found farther south around the edges of the Antarctic shelf.

- A commercially caught Patagonian toothfish weighs between 7–10 kg with large adults weighing around 100 kilograms. They live up to 50 yearsand reach a length up to 2.3 m (7.5 ft).

- Both species are marketed as Chilean sea bass.

World’s Largest Marine Reserve Created Off Antarctica

- In 2016, a remote and largely pristine stretch of ocean off Antarctica received international protection, becoming the world’s largest marine reserve as a coalition of countries came together to protect it.

- South of New Zealand and deep in the Southern Ocean lies the 1.9 million square-mile Ross Sea that is sometimes called the “Last Ocean” because it is largely untouched by humans.

- The Ross Sea is a place of “fish with antifreeze in their blood, penguins that survive the equivalent of a human heart attack on each dive, and seals that must use their teeth to constantly rake open breathing holes in the ice.”

- These waters are vital to the health of the planet since they produce strong upwelling currents that carry critical nutrients north of the equator and play a major role in regulating the climate.

- The new protection went into force on December 1, 2017. Fishing is not allowed in 598,000 square miles of the new reserve (some toothfish fishing is expected to proceed in a specially designated zone in the remainder of the protected area).

By legally altering the name of the waterbody, Scientists want to raise attention to these challenges, as well as the fast warming of the Southern Ocean as a result of global warming.